Beer-cyclopedia

A

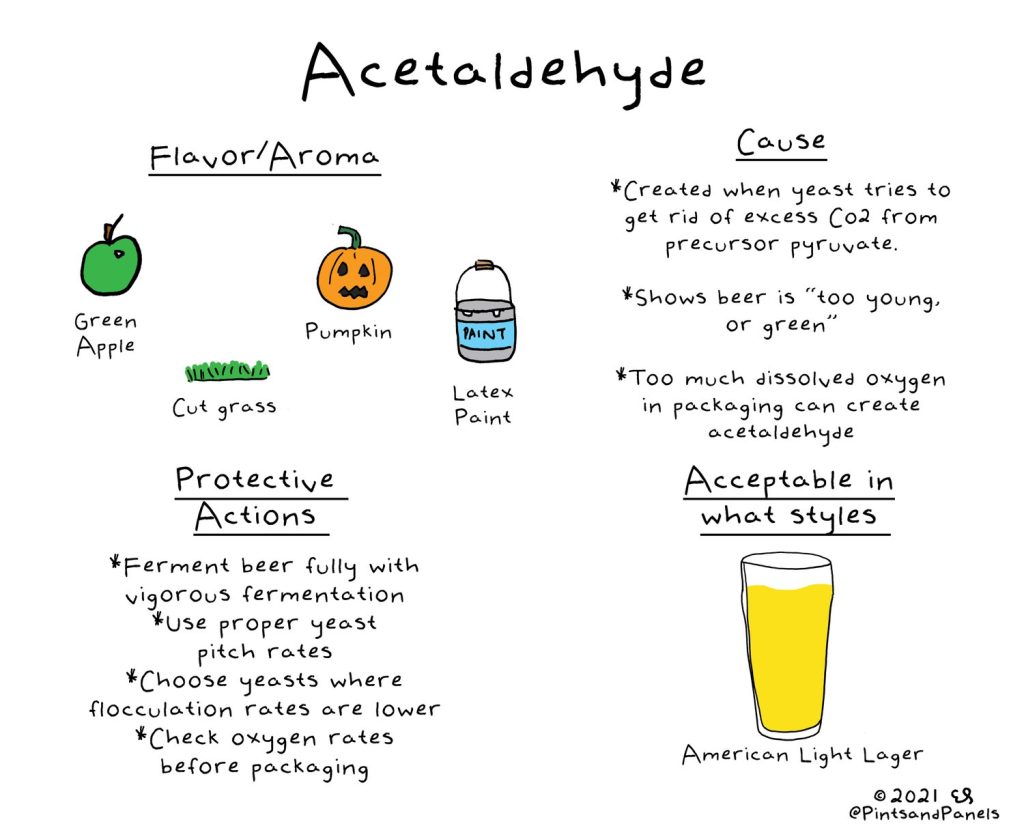

Acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde is a compound that can be present in craft beer, and is often considered a flaw or off-flavor. It is a natural byproduct of the fermentation process, but can also be produced by yeast when they are stressed or when the beer is not properly aged. Acetaldehyde is characterized by a green apple or fresh-cut grass flavor and aroma, and can also give the beer a slick or oily mouthfeel. In small amounts, acetaldehyde is not noticeable and can even contribute to the flavor profile of some beer styles, such as American lagers. However, in higher concentrations, it can be unpleasant and detract from the overall quality of the beer. Brewers can take steps to reduce the presence of acetaldehyde in their beer, such as ensuring healthy yeast conditions and properly conditioning the beer after fermentation.

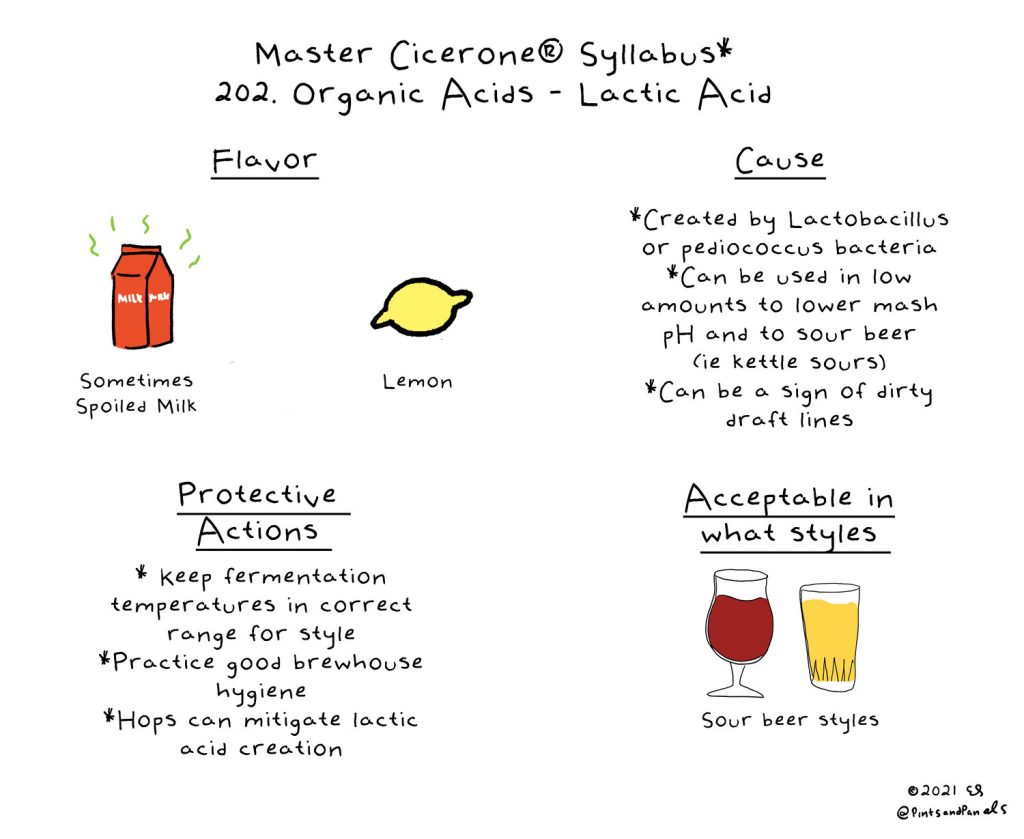

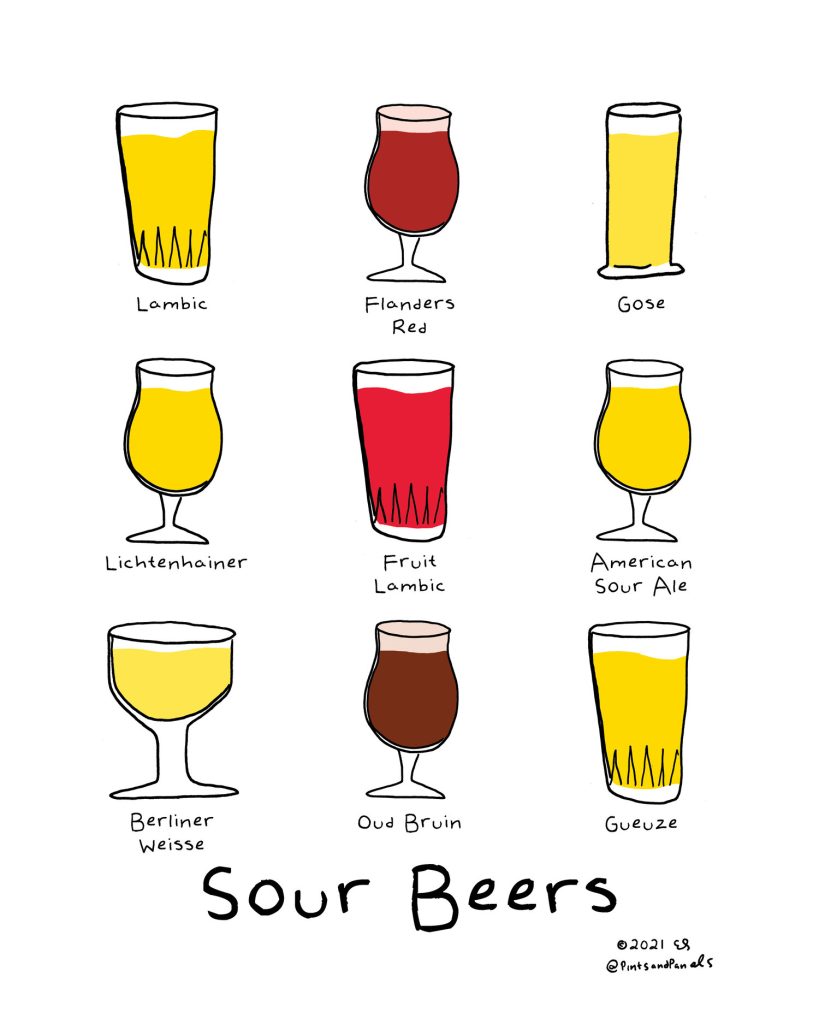

Acid Rest. Acid rest is a step in the mashing process of brewing beer that is intended to break down certain grains and promote the formation of lactic acid. During the mash, which is the process of steeping crushed grains in hot water to extract their sugars, the temperature is gradually increased to activate different enzymes that break down the starches in the grain into fermentable sugars. An acid rest is typically performed at the beginning of the mash, when the temperature is around 95-113°F (35-45°C). At this temperature, certain enzymes are activated that break down phytin, a naturally occurring compound in some grains that can interfere with the brewing process. This step also promotes the growth of certain bacteria that produce lactic acid, which can contribute to the sourness or tartness of the beer. Acid rest is commonly used in the brewing of sour beers, Berliner Weisse, and other styles that require a tart or acidic flavor profile. However, it is not necessary for all beer styles and may not be included in all brewing recipes.

Acrospire is a term used in malting, which is the process of germinating and drying grains to produce malt for brewing beer. During the germination phase, the grain begins to sprout and produce an acrospire, which is a small, white shoot that emerges from the end of the grain kernel. This acrospire contains enzymes that are necessary for the conversion of starches in the grain into fermentable sugars. The length of the acrospire is an important factor in the malting process, as it indicates the degree of modification or enzymatic activity that has taken place in the grain. Once the acrospire has grown to a certain length, typically around 3/4 of the length of the kernel, the maltster halts the germination process by drying the grain. This stops the growth of the acrospire and preserves the enzymatic activity within the malt. The level of modification or degree of enzyme activity in the malt can affect the fermentability and flavor profile of the beer, and can be adjusted through the length of the germination process and the level of drying.

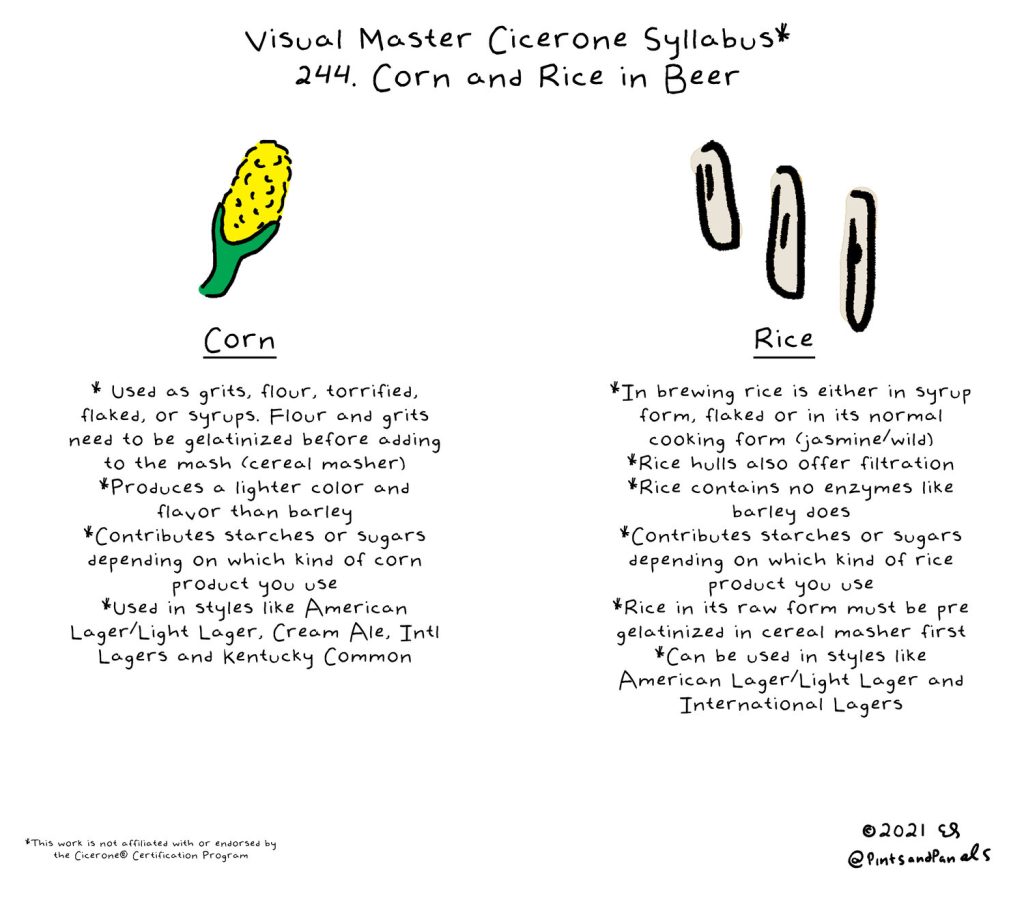

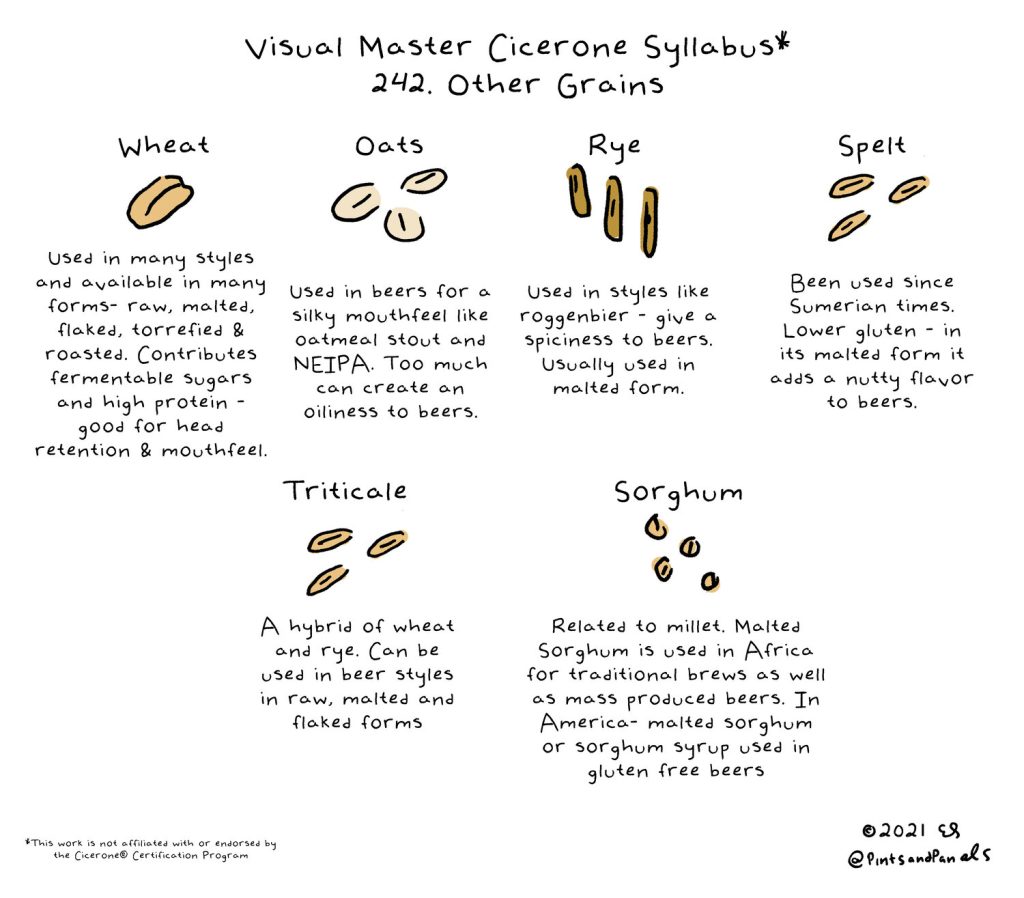

Adjunct. An adjunct in craft beer refers to any ingredient that is added to the brewing process in addition to the traditional four main ingredients of beer: water, malted barley, hops, and yeast. Common adjuncts include corn, rice, wheat, oats, and various sugars such as honey or molasses. Adjuncts can be used to add fermentable sugars to the beer, to lighten the body and color of the beer, to increase the alcohol content, or to add flavor and aroma characteristics. The use of adjuncts is a common practice in American lagers, which often include corn or rice to produce a lighter, crisper beer. However, some craft brewers also use adjuncts in creative ways to enhance the flavor and complexity of their beer. The use of adjuncts in craft beer is a topic of debate among beer enthusiasts, with some arguing that they are essential to certain beer styles while others argue that they can detract from the purity and tradition of beer.

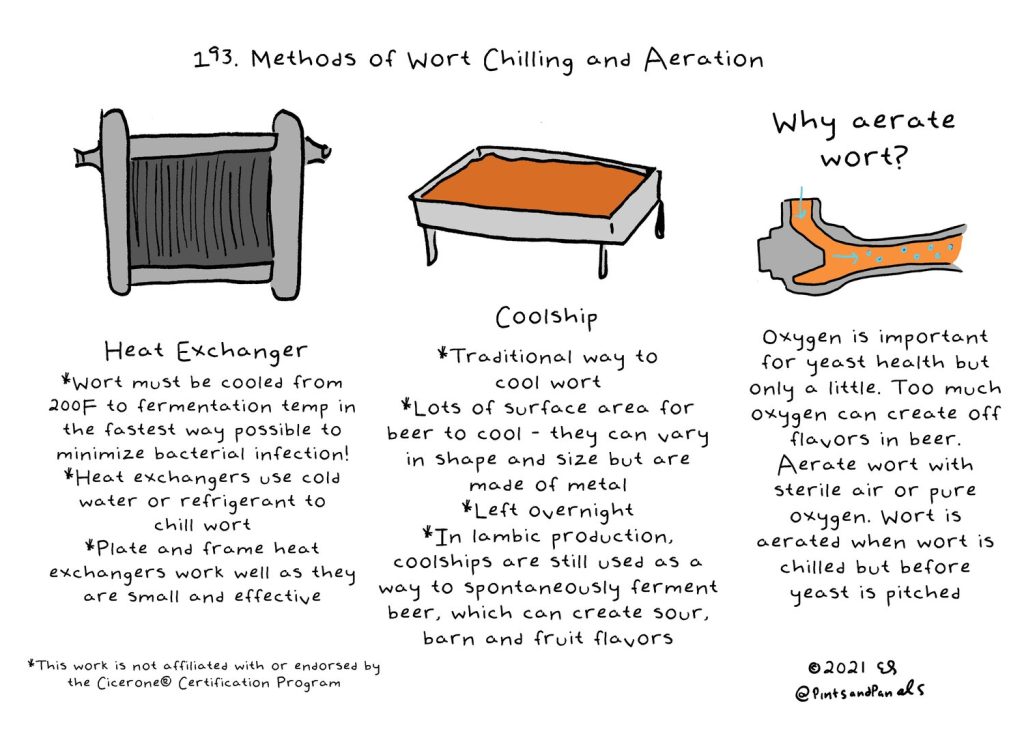

Aeration. Aeration, in the context of brewing craft beer, refers to the process of introducing air or oxygen into the wort (unfermented beer) after it has been cooled and transferred to the fermentation vessel. This is typically done by either splashing or shaking the wort vigorously, or by using an aeration stone or wand to diffuse air or oxygen into the wort. The purpose of aeration is to provide the yeast with the oxygen it needs to reproduce and build cell walls before it begins to ferment the wort. Yeast requires oxygen to synthesize sterols and unsaturated fatty acids, which are important components of cell walls, and a lack of oxygen during the early stages of fermentation can lead to under attenuation, sluggish fermentation, and off-flavors. Aeration is an important step in the brewing process for most beer styles, although some beer styles, such as certain Belgian ales or sour beers, may require limited aeration or none at all.

AHA American Homebrewers Association. The American Homebrewers Association (AHA) is a non-profit organization based in the United States that promotes homebrewing and supports the interests of homebrewers. Founded in 1978, the AHA provides resources and educational materials for homebrewers, including a monthly magazine, online forums, and national and regional competitions. The AHA also advocates for homebrewing rights and works with legislators to ensure that homebrewing is legal and accessible. In addition, the AHA hosts the annual National Homebrew Competition, the world’s largest beer competition, as well as the annual Homebrew Con, a national conference for homebrewers featuring seminars, workshops, and social events. The AHA is a division of the Brewers Association, a trade group that represents small and independent craft brewers in the United States.

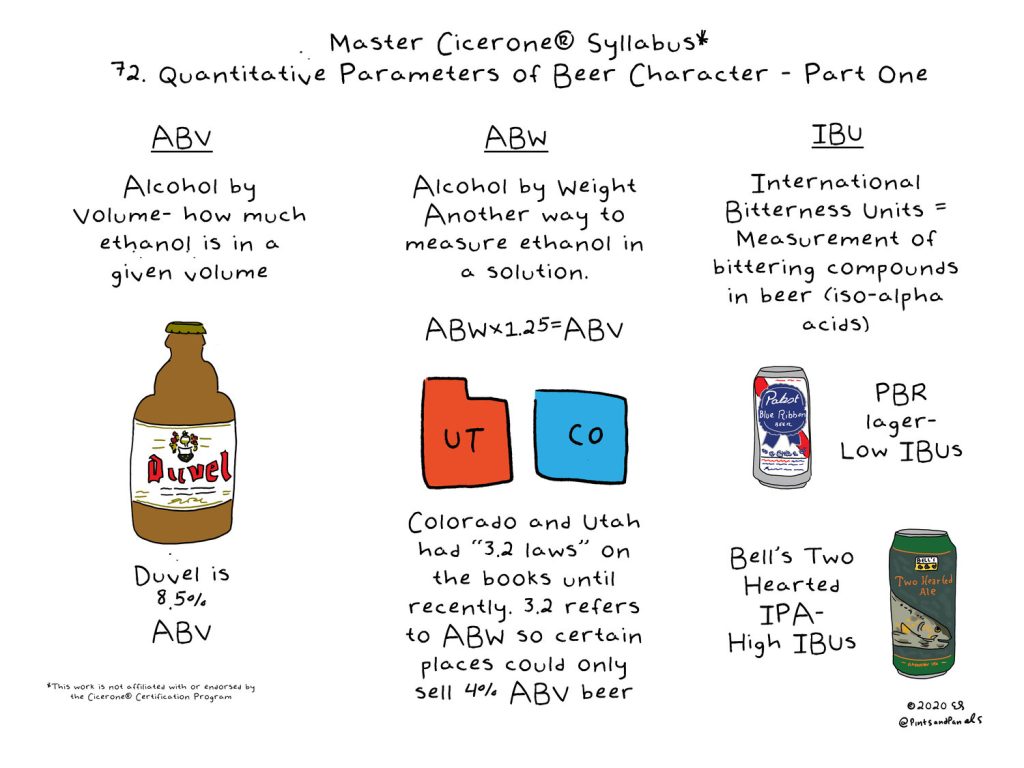

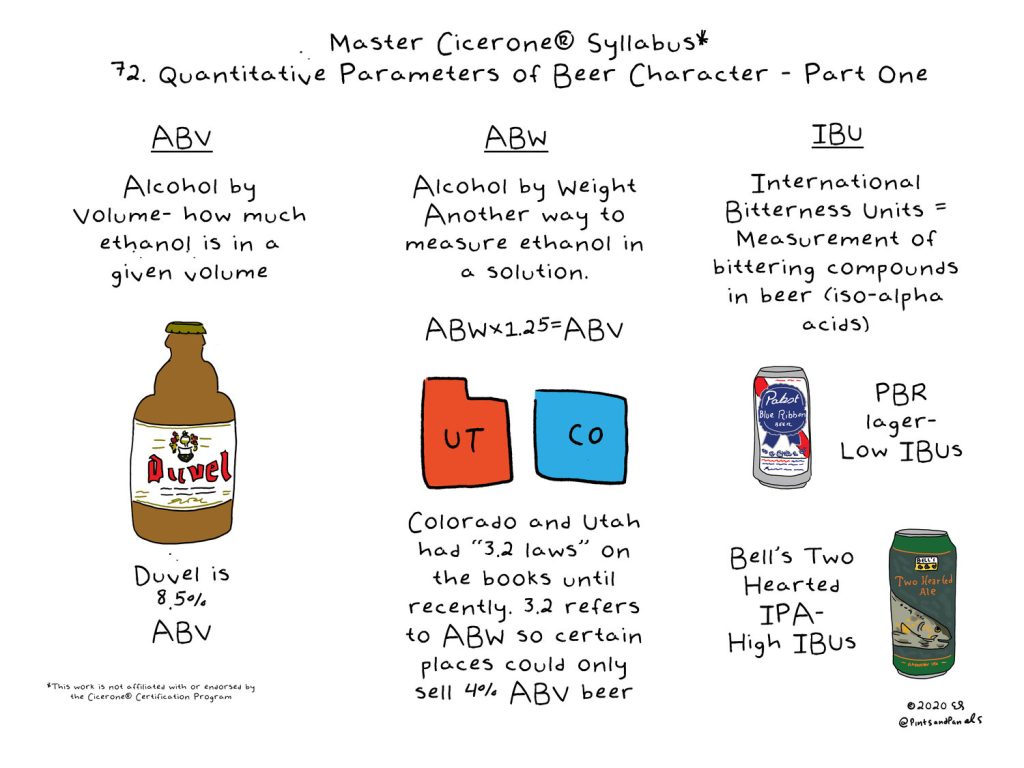

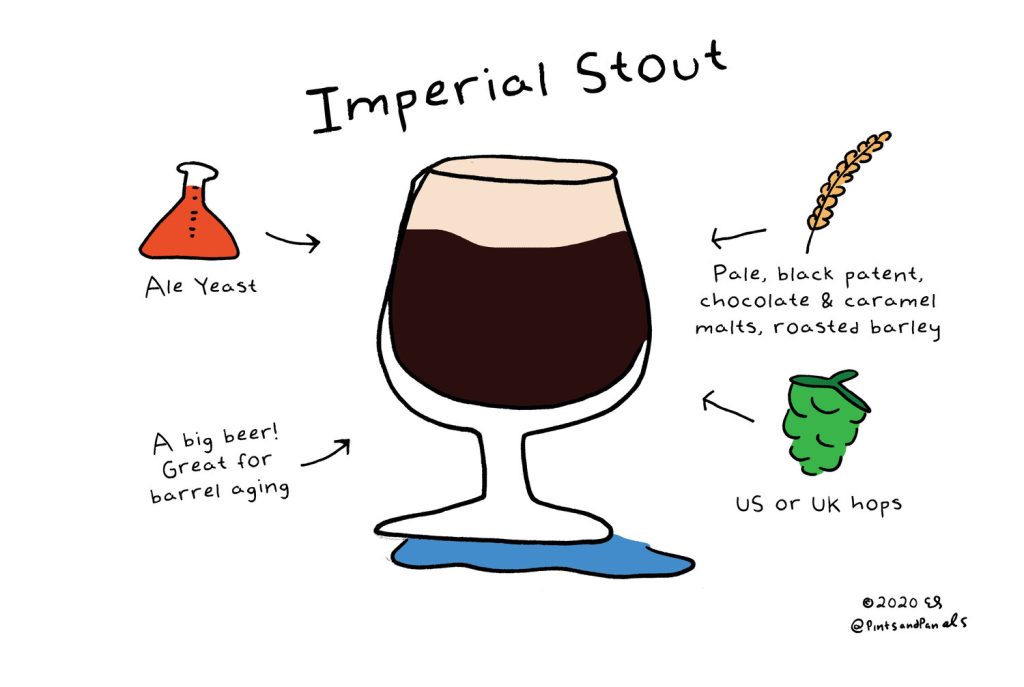

Alcohol. In relation to craft beer, alcohol refers to the ethyl alcohol, or ethanol, that is produced during the fermentation process. Alcohol is a natural byproduct of yeast metabolism, which occurs when the yeast consumes the fermentable sugars in the wort (unfermented beer) and produces ethanol and carbon dioxide. The amount of alcohol in a beer is typically measured as a percentage of the total volume, or ABV (alcohol by volume). The ABV of a beer can vary widely, from less than 3% for some light beers to over 10% for some imperial stouts or barleywines. The alcohol content of a beer can have a significant impact on its flavor and body, with higher ABV beers often having a stronger, more complex flavor and a fuller mouthfeel. However, excessive alcohol consumption can be harmful to health and should be consumed in moderation.

Alcohol by volume (ABV) is a measure of the amount of alcohol present in a given volume of beer, expressed as a percentage. In craft beer, ABV is a commonly used measure of a beer’s strength, as it provides an indication of the amount of ethanol (alcohol) that is present in the beer. ABV is calculated by determining the weight of the alcohol in a given volume of beer, and dividing that by the total weight of the beer. For example, a beer with an ABV of 5% contains 5% alcohol by volume, meaning that 5% of the total volume of the beer is comprised of alcohol. The ABV of a beer can vary widely, depending on factors such as the amount and type of malt used, the strength of the yeast, and the length of the fermentation period. Different beer styles can have different typical ABVs, with some styles, such as session beers, having lower ABVs, while others, such as barleywines or imperial stouts, having higher ABVs.

Alcohol by weight (ABW) is another measure of the alcohol content in beer, but it is less commonly used in the United States compared to Alcohol by volume (ABV). ABW is calculated by dividing the weight of the alcohol in a given volume of beer by the total weight of the beer, and then multiplying that by 100 to get a percentage. For example: 3.2 percent alcohol by weight equals 3.2 grams of alcohol per 100 centiliters of beer. This measure is always lower than Alcohol by Volume. To calculate the approximate alcohol content by weight, subtract the final gravity from the original gravity and divide by 0.0095. For example: 1.050 – 1.012 = 0.038/0.0095 = 4% ABW.

In craft beer, ABW is not typically used as a measure of a beer’s strength as it can be misleading. This is because the weight of alcohol is less than the weight of an equal volume of water, so ABW measurements can make a beer seem weaker than it actually is. For example, a beer with an ABV of 5% would have an ABW of approximately 4%, making it appear weaker than it actually is. Due to this, ABV is the preferred method for measuring alcohol content in craft beer as it provides a more accurate measurement.

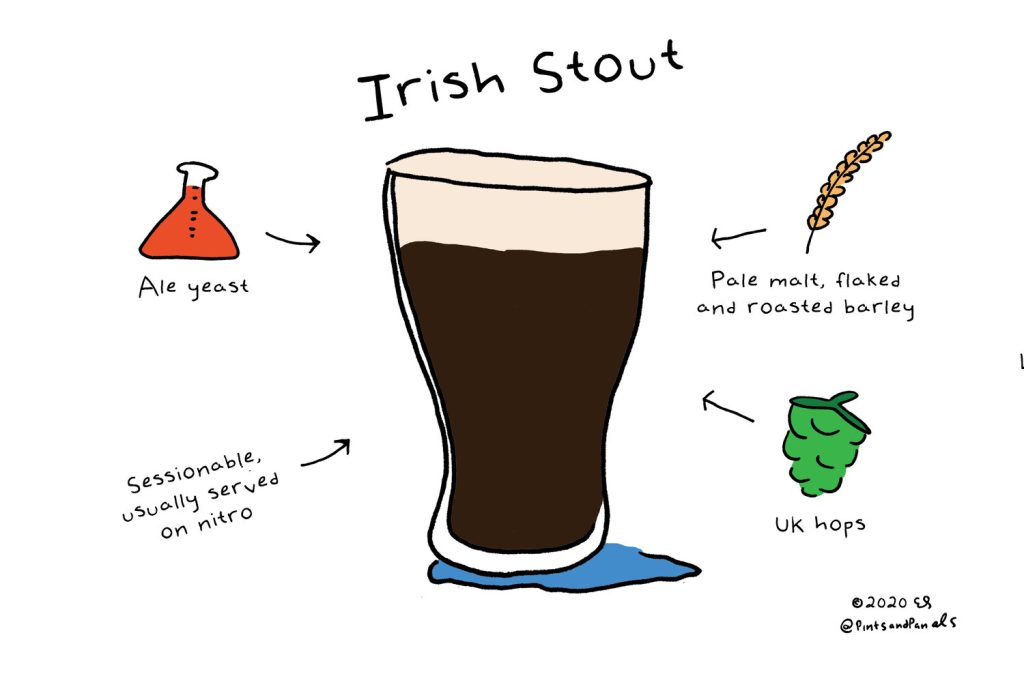

Ale. An ale is a type of beer that is brewed using a warm fermentation process and a specific strain of yeast that ferments at the top of the beer. Ales are characterized by their fruity, robust, and often complex flavors, which are a result of the fermentation process and the use of specific malts, hops, and other ingredients. Ales are typically brewed with a higher amount of malted barley, which gives them a more pronounced malt flavor compared to lagers. Ales can range in color from pale gold to dark brown or even black, and in alcohol content from sessionable strength to high gravity, making them suitable for a variety of occasions and tastes. Examples of ale styles include pale ale, IPA, porter, stout, Belgian-style ale, and many others.

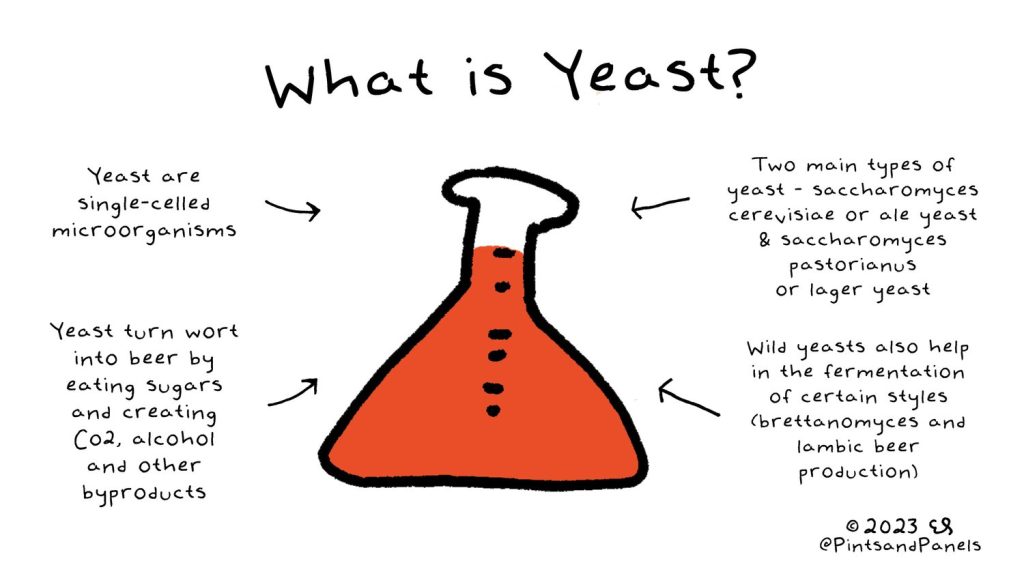

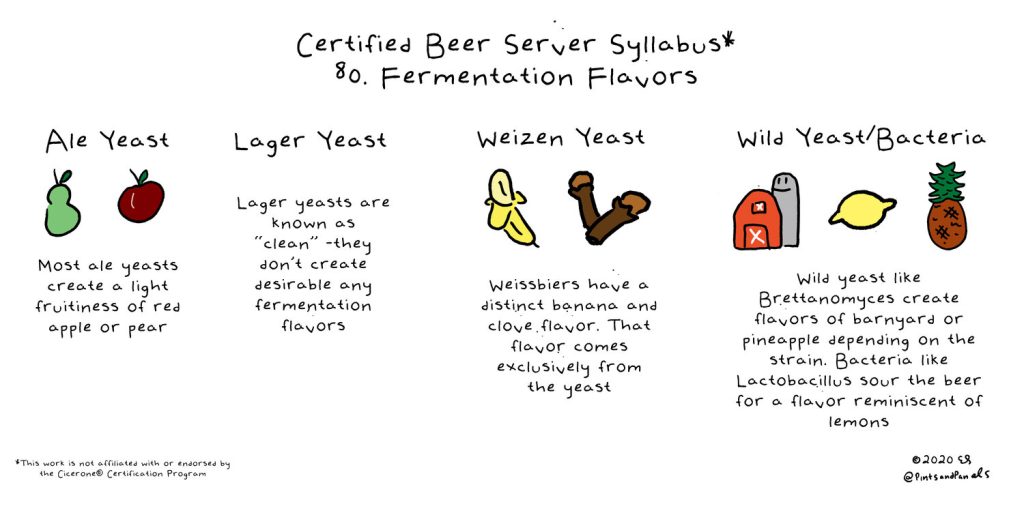

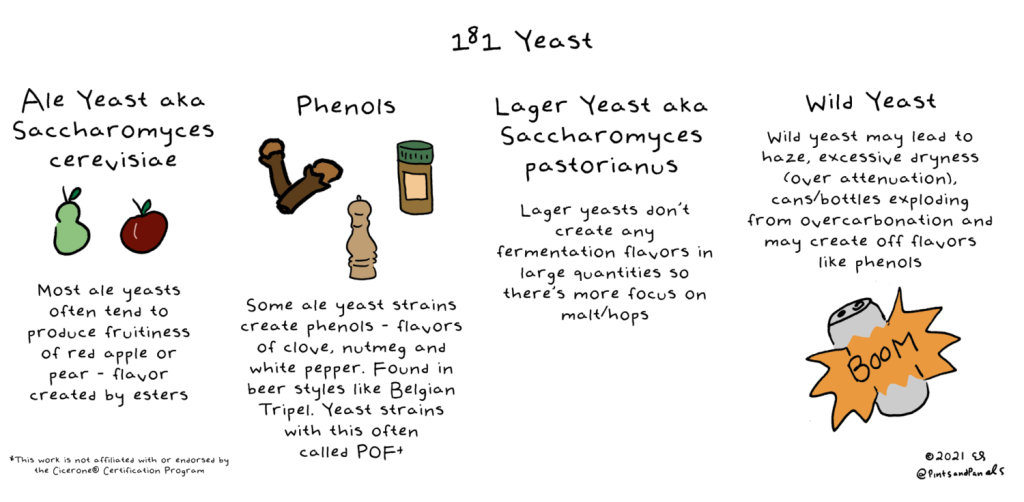

Ale Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Ale yeast is a type of yeast that is specifically used for fermenting ale-style beers. It is a top-fermenting yeast, meaning that it rises to the top of the beer during the fermentation process. Ale yeast typically ferments at warmer temperatures than lager yeast, which results in a faster fermentation process and a greater production of flavor compounds.

There are several different strains of ale yeast, each of which contributes its own unique flavor profile to the finished beer. Some ale yeasts are known for producing fruity, estery flavors, while others can impart spicy or earthy notes. The choice of yeast strain can greatly impact the final flavor and aroma of the beer, and different strains are often chosen to complement specific malt and hop combinations. Ale yeast strains are widely available to homebrewers and commercial brewers alike, and are an essential component of brewing a wide variety of ale styles.

Alpha Acid. Alpha acids are a key component of hops, a plant species that is an essential ingredient in the brewing of beer. Alpha acids are responsible for the bitter taste in beer, which balances the sweetness of the malted barley and other grains used in the brewing process.

In craft beer, alpha acid levels are carefully controlled to achieve the desired bitterness, flavor, and aroma profile of the finished beer. Brewers use different hop varieties that have different alpha acid levels, and they can adjust the alpha acid concentration by varying the amount of hops used, the timing of hop additions, and the method of hop extraction.

The alpha acid concentration of hops is typically measured as a percentage of the total hop weight, and is commonly referred to as “alpha acid units” or “AAUs.” For example, a hop variety with 10% alpha acids would have 1 AAU per 0.1 oz of hops added to the beer.

Knowing the alpha acid content of hops is important for brewers to create consistent and balanced beer.

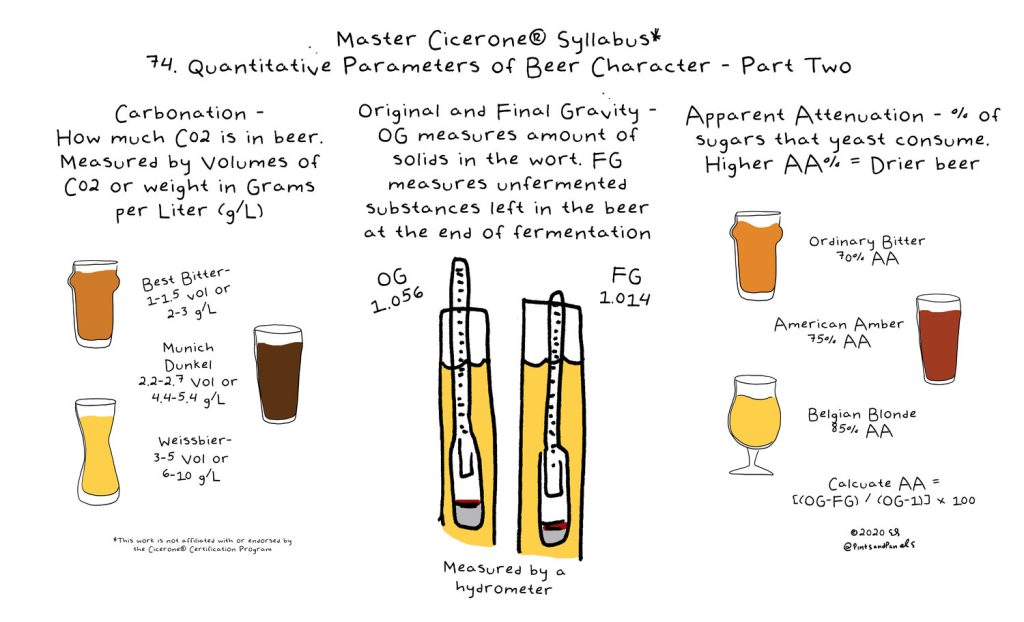

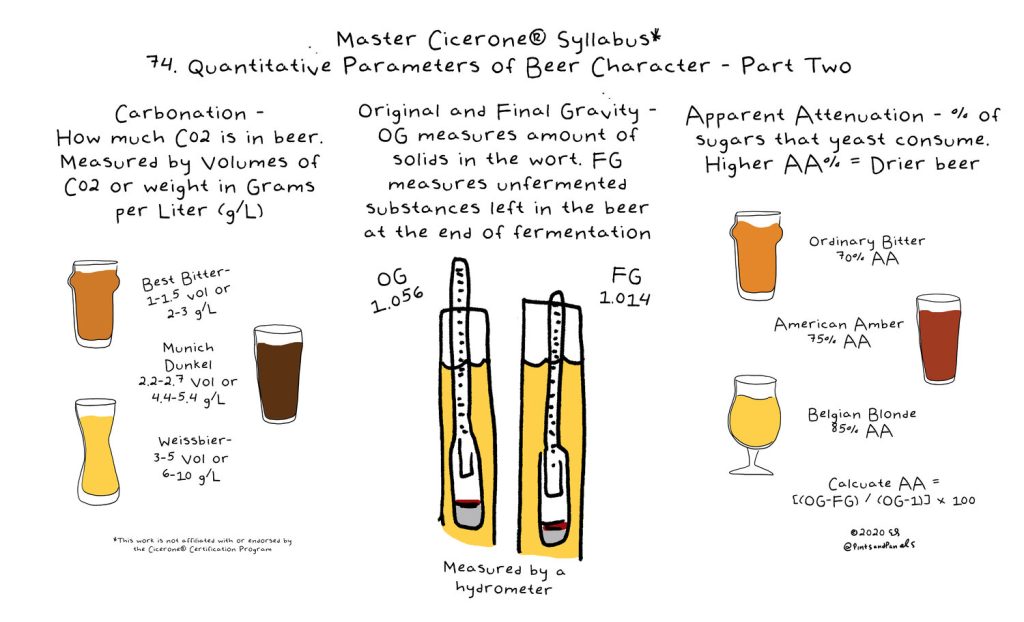

Apparent Attenuation is a measurement used in the brewing industry to determine the amount of sugar that yeast has converted into alcohol and carbon dioxide during the fermentation process. In craft beer, the apparent attenuation is an important factor in determining the final alcohol content, as well as the flavor and mouthfeel of the finished beer.

Apparent attenuation is expressed as a percentage, and it is calculated by comparing the amount of sugar that was originally present in the wort (the mixture of water and malted grains that is fermented to make beer) to the amount of sugar that remains after fermentation. The formula for calculating apparent attenuation is:

((original gravity – final gravity) / original gravity) x 100

where the “original gravity” is the specific gravity (density) of the wort before fermentation, and the “final gravity” is the specific gravity of the beer after fermentation.

For example, if a beer starts with an original gravity of 1.050 and finishes with a final gravity of 1.010, the apparent attenuation would be:

((1.050 – 1.010) / 1.050) x 100 = 80%

This means that the yeast has converted 80% of the available sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide.

Brewers can adjust the apparent attenuation of their beer by selecting specific yeast strains and adjusting the brewing process, such as using different temperatures during fermentation. A higher apparent attenuation will result in a drier, more alcoholic beer, while a lower apparent attenuation will result in a sweeter, less alcoholic beer.

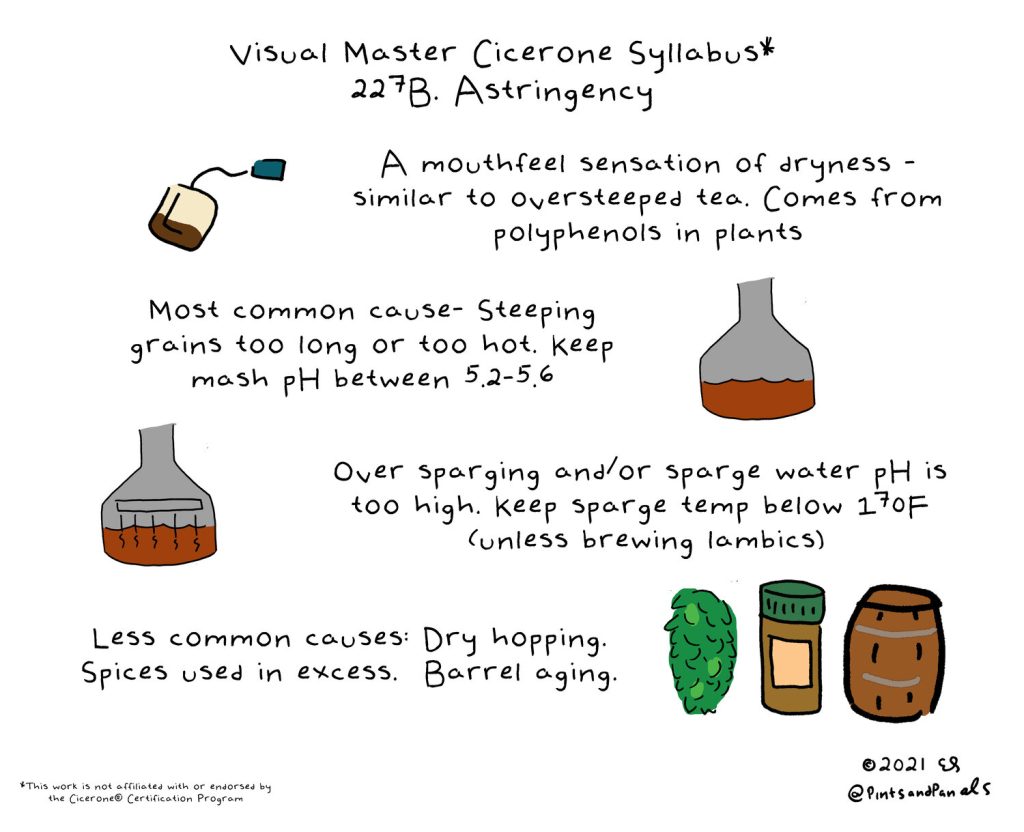

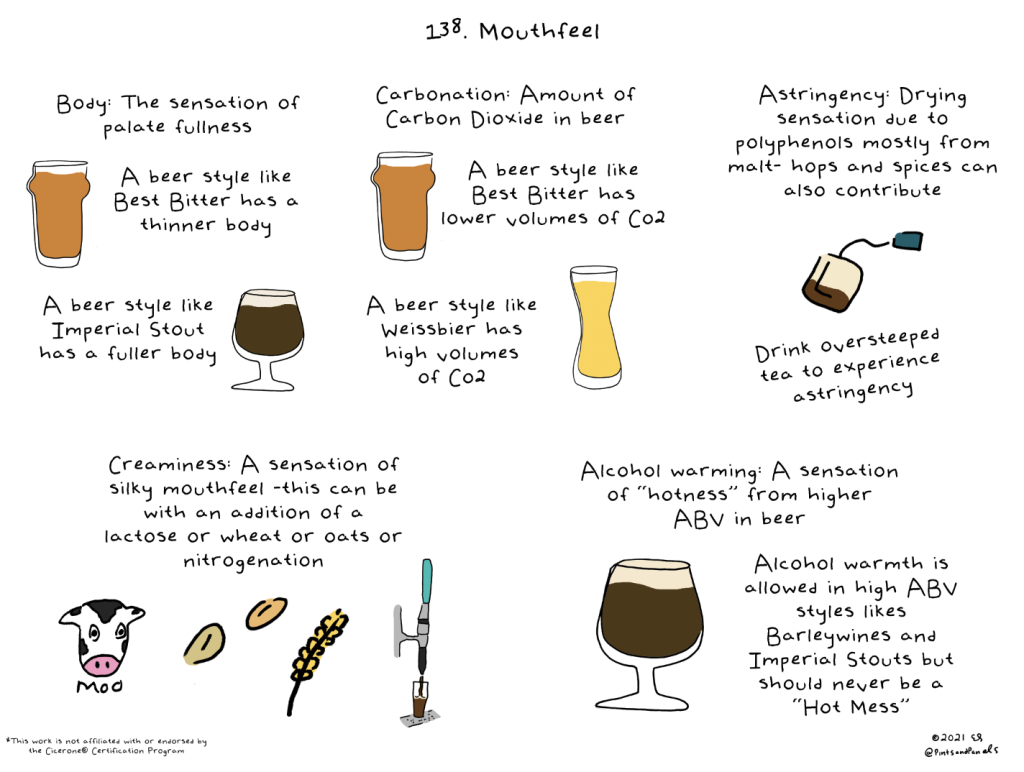

Astringency is a sensory characteristic that can be found in craft beer, which is often described as a dry, puckering, and sometimes bitter or harsh sensation on the palate. Astringency is caused by the interaction between tannins and proteins in beer, which can lead to a rough or drying sensation in the mouth.

Tannins are a type of polyphenolic compound that are naturally present in many ingredients used in beer brewing, such as malted grains, hops, and oak barrels used for aging. When these tannins interact with proteins in the beer, they can create a sensation of dryness and roughness on the palate, which is perceived as astringency.

Astringency can be desirable in some styles of beer, such as certain types of Belgian ales or sour beers, where it is used to balance sweetness or create complexity. However, excessive astringency can be unpleasant and overwhelming, and can negatively impact the overall flavor and drinkability of the beer.

Brewers can control astringency in their beer by adjusting the ingredients and brewing process. For example, they can use different varieties of hops that are lower in tannins, or modify the mash and sparging process to reduce the extraction of tannins from the malted grains. Careful attention to pH levels during brewing can also help to minimize astringency.

Attenuation in craft beer refers to the degree to which the yeast has consumed the fermentable sugars in the wort during the fermentation process. Attenuation is expressed as a percentage, and it can have a significant impact on the final alcohol content, flavor, and mouthfeel of the finished beer.

During fermentation, yeast consumes the sugars in the wort and converts them into alcohol and carbon dioxide. The degree to which the yeast consumes these sugars depends on several factors, such as the type of yeast used, the temperature of fermentation, and the composition of the wort.

Attenuation is calculated by comparing the original gravity (OG) of the wort, which is a measure of the density of the wort before fermentation, to the final gravity (FG) of the beer, which is a measure of the density of the beer after fermentation. The formula for calculating attenuation is:

((OG – FG) / OG) x 100

For example, if the OG of the wort is 1.050 and the FG of the finished beer is 1.010, the attenuation would be:

((1.050 – 1.010) / 1.050) x 100 = 80%

This means that the yeast has consumed 80% of the available fermentable sugars in the wort.

Higher attenuation levels result in a drier beer with a lower final gravity and a higher alcohol content. Lower attenuation levels result in a sweeter beer with a higher final gravity and a lower alcohol content. Brewers can control the attenuation of their beer by selecting specific yeast strains and adjusting the brewing process, such as controlling the fermentation temperature or using different types of malted grains.

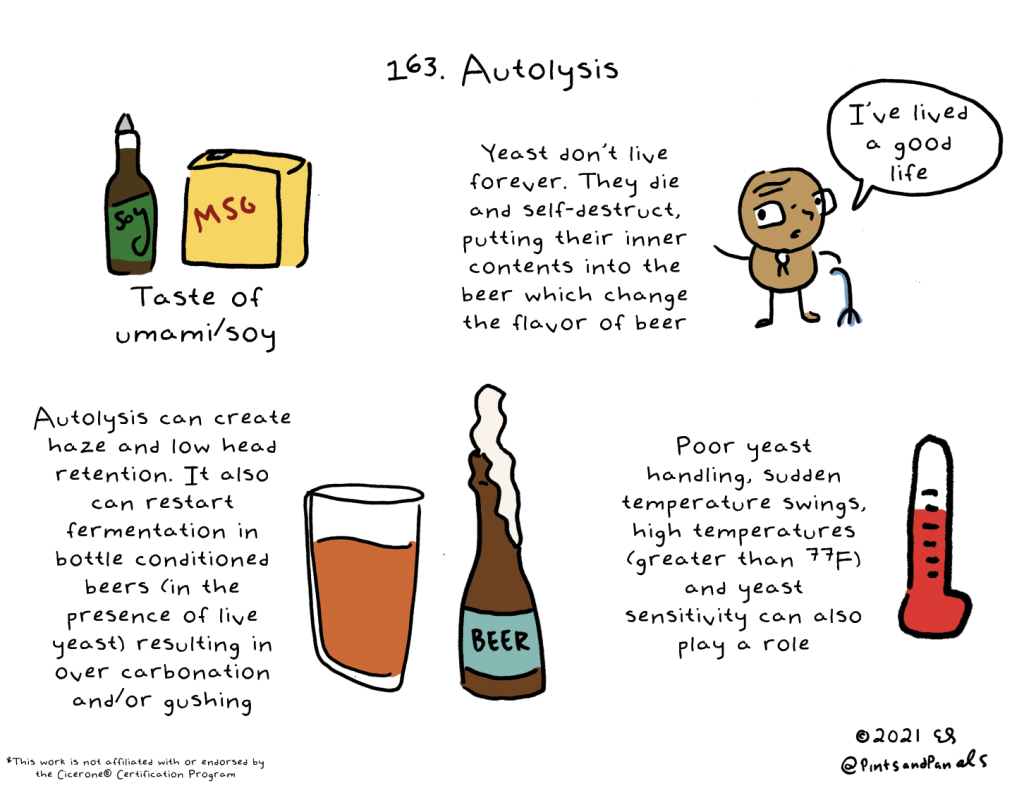

Autolysis is a natural process that occurs during the brewing of beer and refers to the self-degradation of yeast cells after they have completed their fermentation duties. Autolysis occurs when yeast cells rupture and release enzymes that break down the cell’s contents, including proteins, amino acids, and nucleic acids.

If left unchecked, autolysis can negatively affect the quality of the beer, as it can result in off-flavors and aromas that are described as being meaty, rubbery, or rotten. Autolysis can also lead to a loss of clarity and stability in the finished beer.

To prevent autolysis, brewers typically remove the beer from contact with the yeast as soon as fermentation is complete, either by transferring it to a separate vessel or by using modern brewing equipment that separates the yeast from the beer automatically. By doing so, the yeast cells are not left in contact with the beer for an extended period, minimizing the risk of autolysis.

Additionally, some yeast strains are more prone to autolysis than others, and brewers will select strains that are less likely to undergo autolysis to reduce the risk further. The brewing process can also be adjusted to reduce the stress on the yeast during fermentation, which can also minimize the risk of autolysis.

B

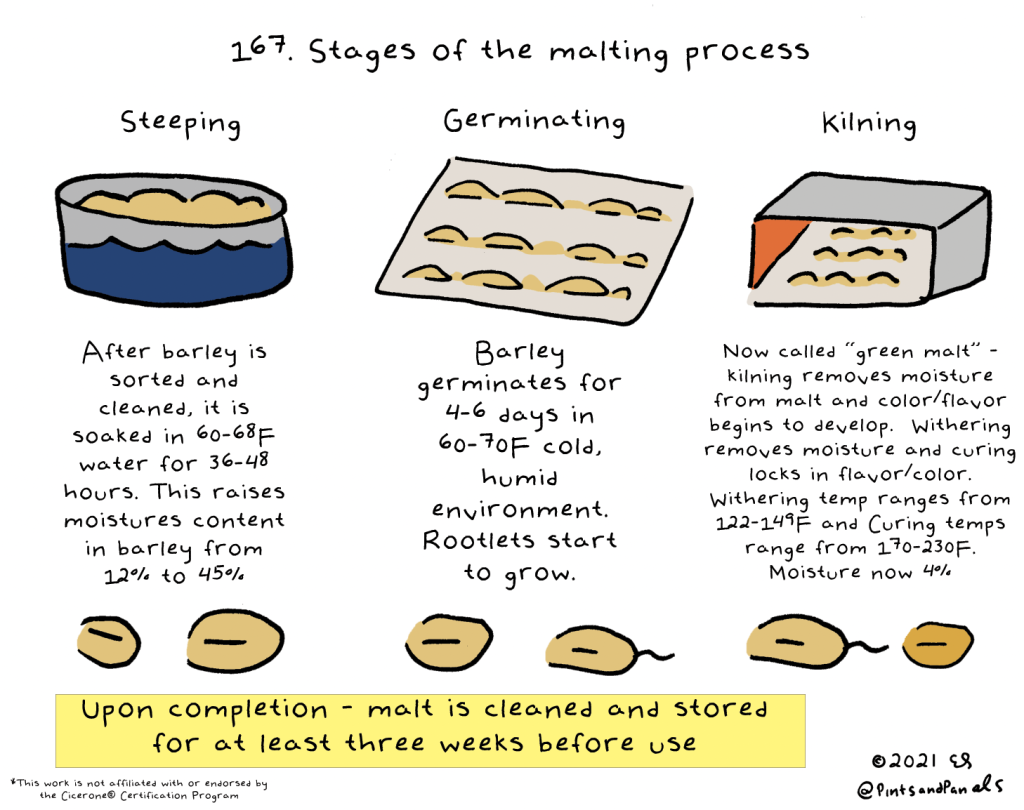

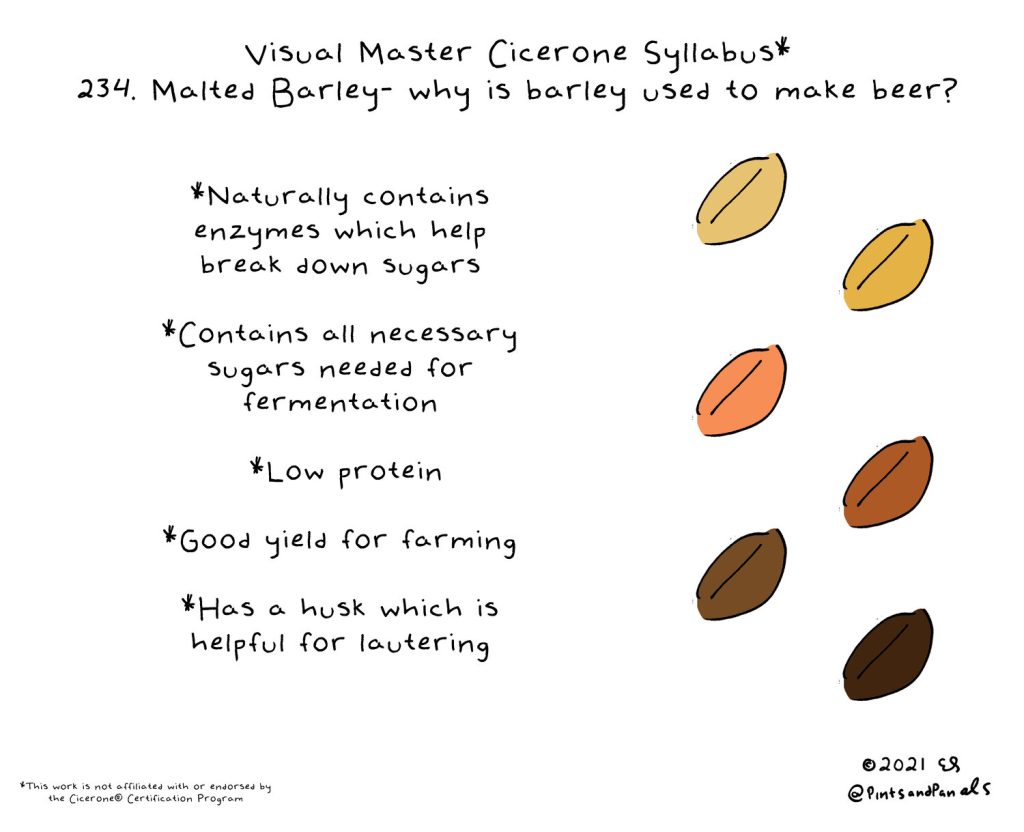

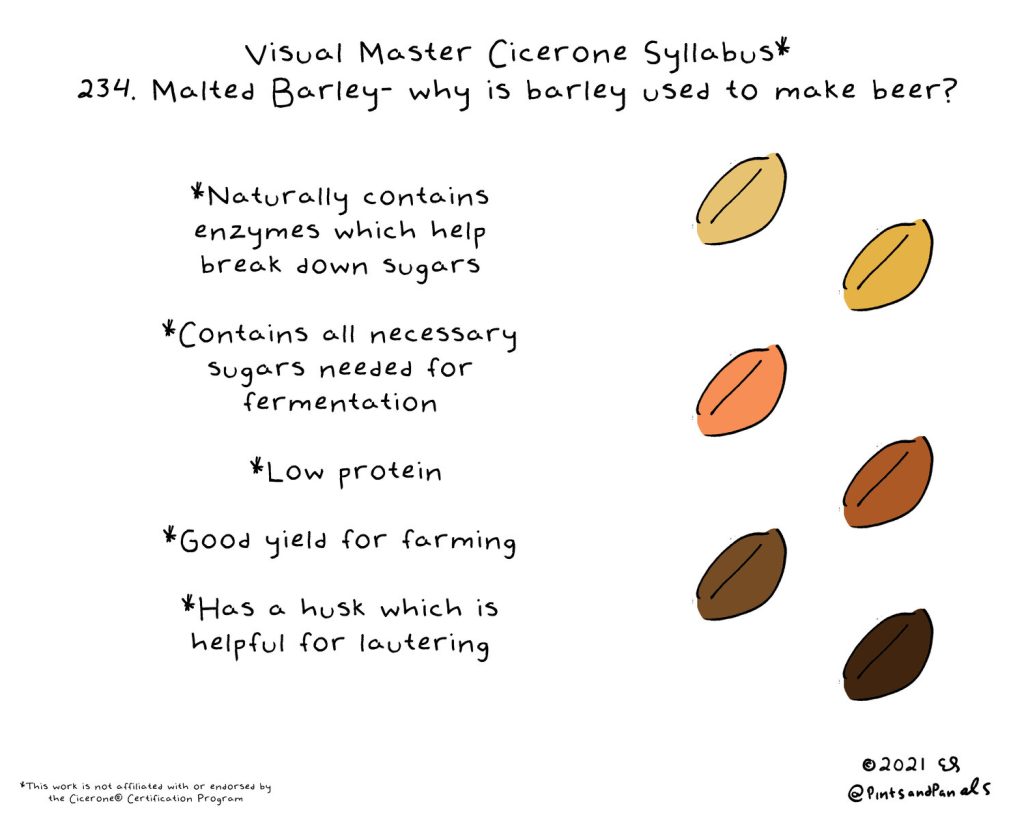

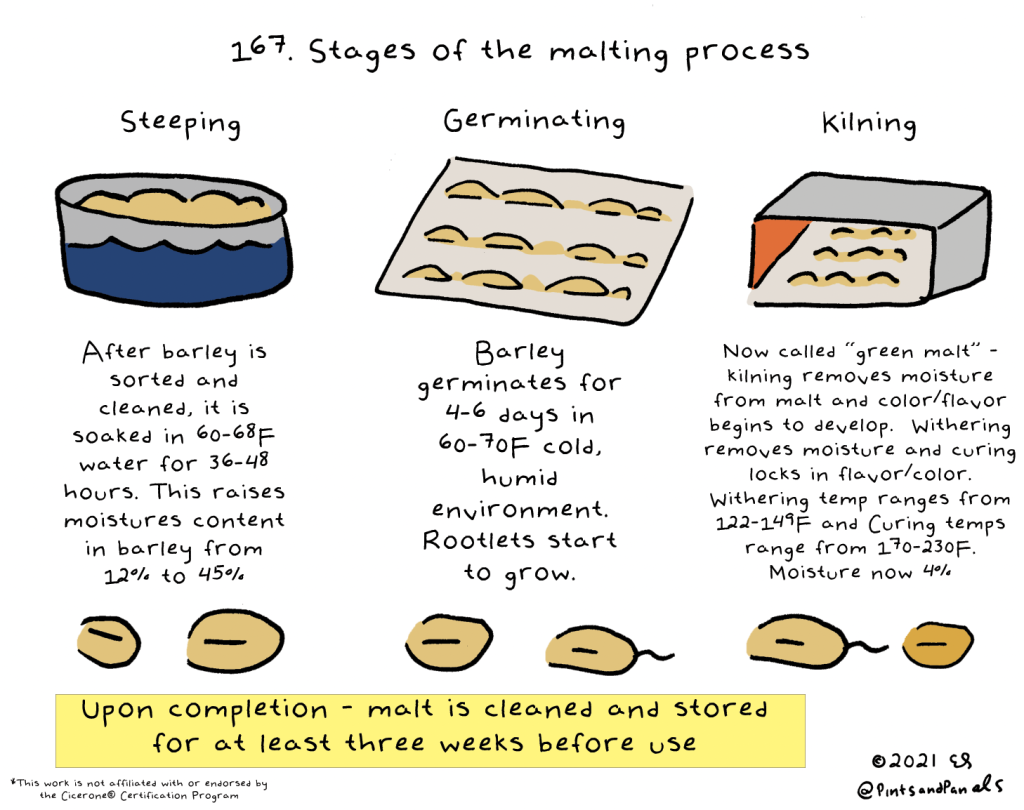

Barley is a type of cereal grain that is used extensively in the production of craft beer. It is a key ingredient in the brewing process and provides the sugars that yeast consumes to produce alcohol.

Barley is a particularly suitable grain for brewing because it contains high levels of starch that can be easily converted into fermentable sugars. The brewing process begins by steeping the barley in water to initiate germination, a process known as malting. This causes the barley to produce enzymes that break down the starches into simpler sugars.

Once the barley has been malted, it is kilned to stop the germination process and to dry the grain. The level of kilning can impact the flavor of the final beer, with darker malts producing more roasted, nutty, or chocolatey flavors and lighter malts producing more subtle flavors.

In the brewing process, the malted barley is crushed and mixed with hot water in a process known as mashing. This creates a sugary liquid called wort, which is boiled with hops to add bitterness and flavor. After boiling, the wort is cooled and yeast is added to begin the fermentation process, where the yeast consumes the sugars and produces alcohol and carbon dioxide.

Different types of barley can be used in brewing, and the specific variety can affect the flavor, color, and aroma of the finished beer. Some examples of barley varieties used in brewing include two-row and six-row barley, Maris Otter, and Golden Promise. In addition to being used in craft beer, barley is also used in the production of other alcoholic beverages such as whiskey and sake.

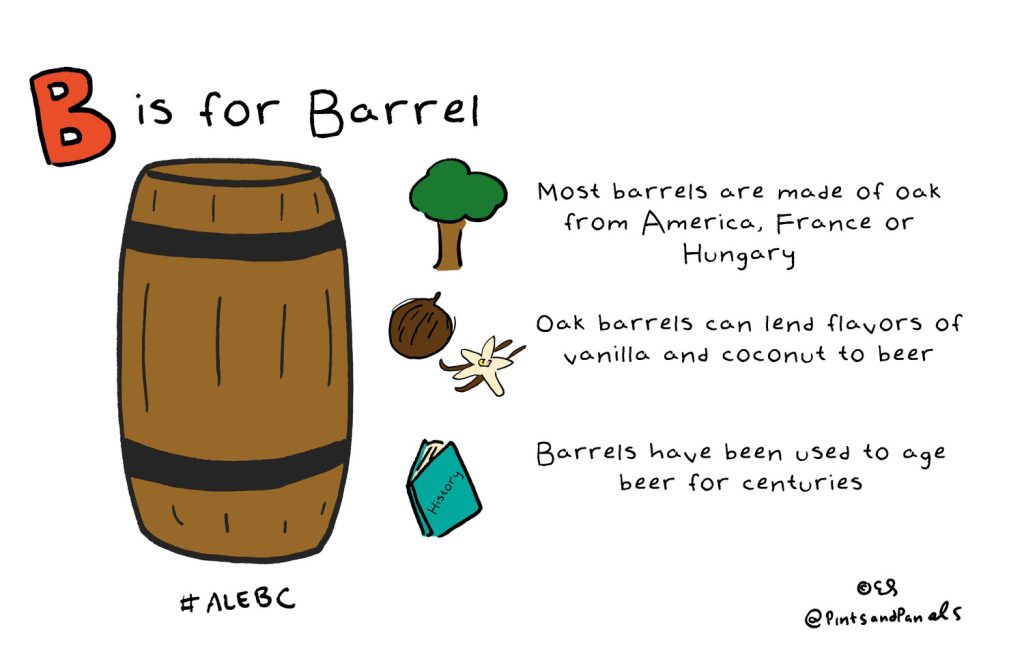

Barrel. In craft beer, a barrel refers to one of two definitions

- a unit of measurement used to describe the volume of beer produced. Or

- Vessel with which to age beer.

Barrel as a unit of measurement. One barrel of beer is equivalent to 31 gallons or 117.35 liters.

The barrel is derived from the traditional wooden barrels that were used to transport and store beer in the past. These barrels were typically made of oak and had a capacity of around 31 gallons. Today, most craft breweries use stainless steel tanks or kegs instead of wooden barrels, but the term “barrel” is still used as a unit of measurement.

The barrel measurement is used by breweries to describe the amount of beer they produce and to calculate the production costs. For example, if a brewery produces 2,000 barrels of beer in a year, it means they have produced a total of 62,000 gallons of beer.

The barrel measurement is also used in the pricing and selling of beer. When a brewery sells beer to a distributor or retailer, the price is often quoted in terms of dollars per barrel. This allows for easy comparison of different beer prices and helps breweries to manage their costs and profitability.

Barrel as a vessel for the beer aging process. Wooden barrels used in fermentation- In modern craft beer brewing, barrels are typically not used to ferment beer, but they are sometimes used to age beer or to impart specific flavors and aromas to the finished product.

When barrels are used for aging or flavoring beer, they are usually made of wood, typically oak, and they may have previously been used to store other beverages such as wine or whiskey. The wood of the barrel can influence the flavor of the beer by imparting flavors such as vanilla, coconut, or oak, as well as adding tannins, which can create a dry, puckering sensation in the mouth.

To use a barrel for aging beer, the beer is usually fermented in a separate vessel, such as a stainless steel tank, and then transferred to the barrel for aging. During aging, the beer absorbs flavors from the wood and any residual spirits or wine that may have been in the barrel previously. The beer may also undergo additional fermentation or conditioning while in the barrel, as wild yeasts and bacteria can sometimes be present in the wood.

Barrel-aging can be a lengthy process, with beers sometimes aging for several months or even years. During this time, the beer is carefully monitored to ensure that it is developing the desired flavors and that there is no contamination or spoilage.

After aging, the beer is usually removed from the barrel and either packaged for sale or blended with other beers to create a unique flavor profile. Some barrel-aged beers are also carbonated and served on tap, while others are sold in bottles or cans.

It’s important to note that barrel aging is a complex and nuanced process that requires a great deal of skill and experience on the part of the brewer. Not all beers are suitable for barrel aging, and it’s important to carefully consider the type of barrel, the length of aging, and other factors when attempting to create a barrel-aged beer.

Beta Acids are one of the two main classes of acids found in the resin glands of the hop plant (Humulus lupulus), which is a key ingredient in craft beer. The other class of acids is alpha acids.

Beta acids are typically found in smaller quantities in hops than alpha acids, and they are less soluble in wort (the liquid extracted from malted grains during the brewing process) than alpha acids. However, they are still an important component of hops, and they can contribute to the bitterness, aroma, and flavor of beer.

When hops are added to boiling wort during the brewing process, the beta acids are isomerized, meaning that they are transformed into a more soluble and bitter form. The amount of beta acids in the hops, as well as the timing and duration of their addition to the wort, can influence the bitterness, flavor, and aroma of the finished beer.

In addition to their contribution to bitterness, beta acids can also contribute to the flavor and aroma of beer. Some of the compounds derived from beta acids, such as humulene and caryophyllene, can produce spicy or woody aromas, while others, such as linalool, can produce floral or citrusy aromas.

Like alpha acids, beta acids are also important for their antimicrobial properties, which can help to prevent the growth of unwanted bacteria in the beer. However, unlike alpha acids, which can contribute to the formation of undesirable compounds in beer when they degrade over time, beta acids are generally more stable and do not pose the same risk of off-flavors or aromas.

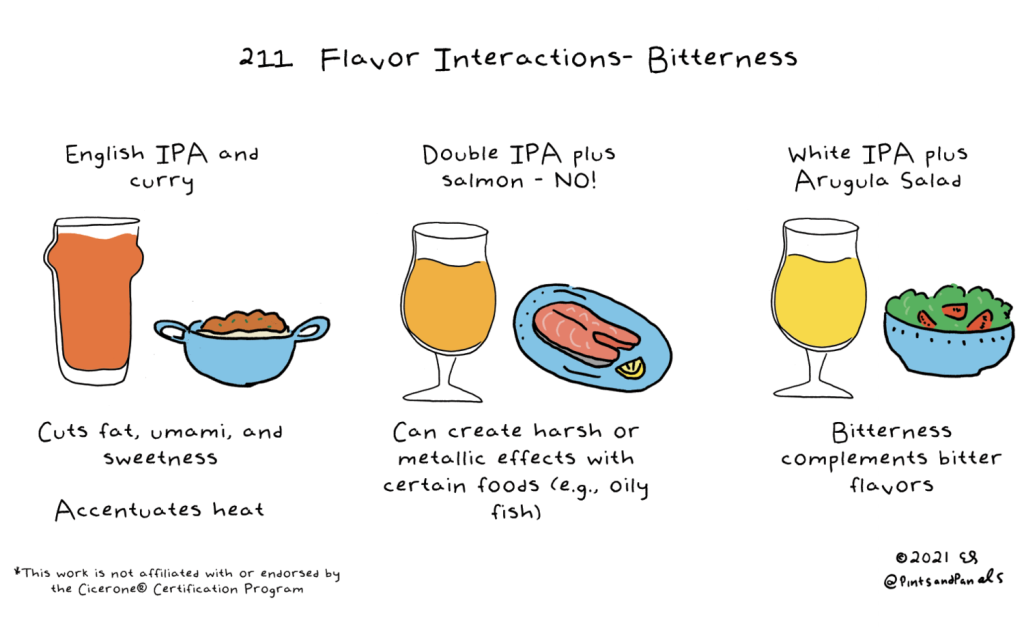

Bitterness (Flavor In beer), is one of the key sensory attributes of beer and refers to the taste sensation that is caused by the presence of bitter compounds in the beer, typically derived from the hops. In craft beer, bitterness is an important component of the overall flavor profile of the beer and is often balanced with other flavors such as sweetness, maltiness, and fruitiness.

The bitterness in craft beer is primarily caused by the presence of alpha acids in the hops, which are isomerized (i.e. transformed into a more soluble and bitter form) during the boiling stage of the brewing process. The degree of bitterness in the beer can be controlled by adjusting the amount of hops used, the duration of the boiling process, and the timing of hop additions during the brewing process.

The level of bitterness in beer is typically measured in International Bitterness Units (defined below) (IBUs), which is a standardized scale that quantifies the amount of iso-alpha acids (the isomerized form of alpha acids) present in the beer. IBUs can range from very low levels (less than 10) in some types of beer, such as a Belgian Witbier, to very high levels (over 100) in some types of India Pale Ales (IPAs) and Imperial Stouts.

Bitterness is an important aspect of craft beer because it can contribute to the overall balance of the beer and can help to accentuate other flavors and aromas. However, excessive bitterness can be unpleasant and overwhelming to the palate, so it is important for brewers to carefully balance the bitterness with other sensory attributes of the beer.

Bitterness Units (BU) Same as International Bitterness Units (IBU). Bitterness Units (BU) are a standardized measurement of the bitterness in beer, particularly in relation to the amount of hops used in the brewing process. The International Bitterness Units (IBU) scale is the most commonly used system for measuring bitterness in craft beer and is based on the concentration of iso-alpha acids in the beer.

Iso-alpha acids are bitter compounds that are formed when the alpha acids found in hops are isomerized during the brewing process. The concentration of iso-alpha acids in beer can be determined by chemical analysis, and this concentration is then used to calculate the IBU value of the beer.

The IBU scale ranges from 0 to over 100, with lower values indicating less bitterness and higher values indicating more bitterness. Different beer styles have different typical ranges of IBUs, with some styles such as pale ales and IPAs being known for their higher bitterness levels, while others such as wheat beers and sour beers may have lower bitterness levels.

It’s important to note that the perceived bitterness of a beer can be influenced by a number of factors, including the sweetness and maltiness of the beer, the carbonation level, and the temperature at which the beer is served. Additionally, individual taste preferences can vary widely, so while the IBU scale provides a useful reference point for measuring bitterness in beer, it is not necessarily a definitive measure of the overall taste and enjoyment of the beer.

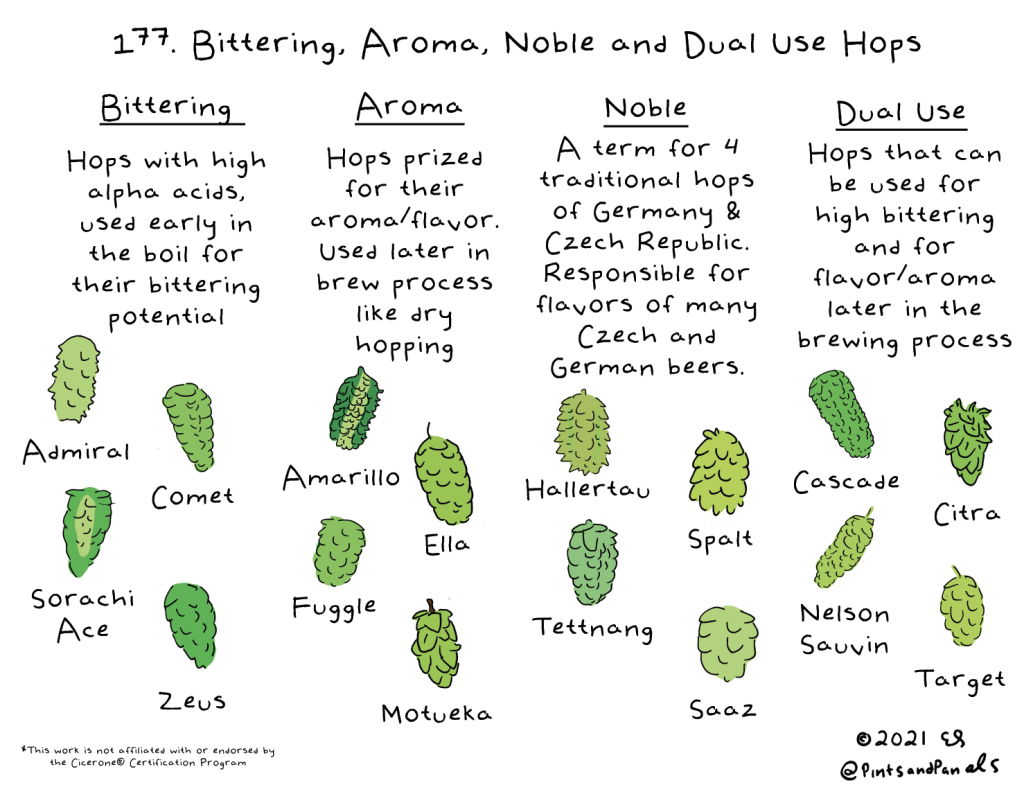

Bittering Hops are a variety of hop that is used primarily for their ability to impart bitterness to craft beer. Hops are a key ingredient in beer and are added during the brewing process to contribute a variety of flavors and aromas, as well as to balance the sweetness of the malted barley with bitterness.

Bittering hops contain a higher level of alpha acids, which are bitter compounds that are isomerized during the brewing process to create the bitter flavor in beer. Bittering hops are typically added to the boiling wort early in the brewing process to allow for maximum isomerization of the alpha acids.

While bittering hops are not typically known for their aroma or flavor contributions to beer, they can have a subtle influence on the overall character of the beer. Some varieties of bittering hops may impart floral or spicy aromas, for example, while others may contribute a slightly herbal or earthy flavor.

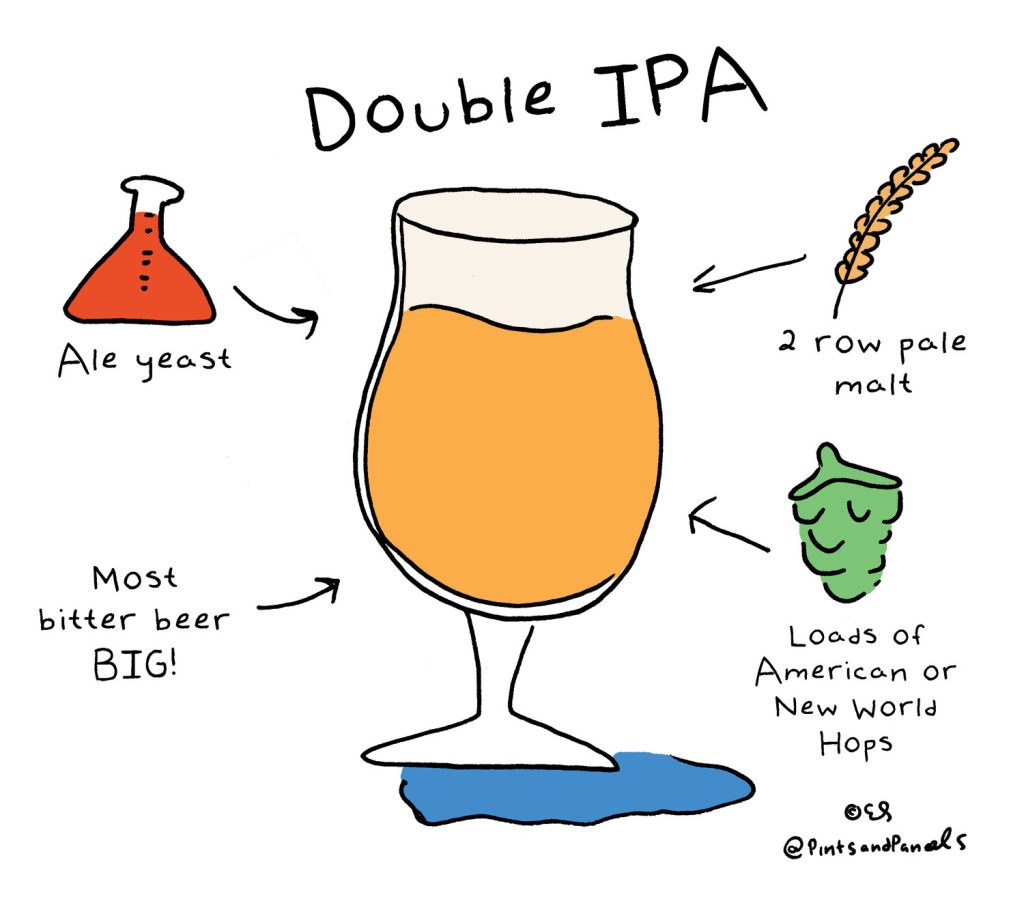

Bittering hops are commonly used in a variety of beer styles, but are particularly important in styles that are known for their bitterness, such as India Pale Ales (IPAs), Double IPAs (DIPAs), and Imperial Stouts. The specific variety of bittering hop used can have a significant impact on the overall bitterness and flavor of the beer, so brewers may experiment with different varieties and combinations of hops to achieve the desired balance and complexity of flavors.

BJCP Beer Judge Certification Program. The BJCP (Beer Judge Certification Program) is a non-profit organization based in the United States that was founded in 1985. The BJCP was established to provide a standardized system of beer judging and to promote beer education and appreciation.

BJCP Beer Judge Certification Program. The BJCP (Beer Judge Certification Program) is a non-profit organization based in the United States that was founded in 1985. The BJCP was established to provide a standardized system of beer judging and to promote beer education and appreciation.

The BJCP offers a certification program for individuals who wish to become certified beer judges. The program consists of a series of exams that test the individual’s knowledge of beer styles, brewing techniques, and sensory evaluation skills. The exams are divided into three levels: Certified, National, and Master.

The BJCP also provides guidelines for beer styles, which are used by judges to evaluate beers in competition. These guidelines are regularly updated and provide detailed information on the aroma, flavor, appearance, and other characteristics of each beer style, as well as information on the ingredients and brewing techniques used to produce each style.

In addition to its certification program and style guidelines, the BJCP also hosts and promotes beer competitions and provides educational resources for brewers, judges, and beer enthusiasts. The organization has a global reach, with certified judges and competitions held around the world.

Blending refers to the process of mixing different batches or barrels of beer together to create a final product with a specific flavor profile or character. Blending can be used to adjust the flavor, aroma, color, and mouthfeel of a beer to achieve a specific balance or to enhance certain characteristics.

Blending can be done at various stages of the brewing process, from the initial fermentation to the aging and packaging stages. Brewers may blend different batches of beer to create a consistent flavor profile from batch to batch, or to create a unique and complex beer that cannot be achieved with a single batch.

Blending can also be used to create a “house blend” for a brewery, which is a consistent and recognizable beer that is brewed from a blend of different batches or barrels. This can help to build brand recognition and loyalty among consumers.

Blending can be done with a variety of beer styles, including sour beers, barrel-aged beers, and hoppy beers like IPAs. Barrel-aged beers are often blended to create a final product with a consistent flavor profile or to add complexity and depth to the beer.

Blending is a technique that requires skill and experience, as different batches or barrels of beer may have different flavor profiles and characteristics that need to be carefully balanced and blended together to achieve the desired result.

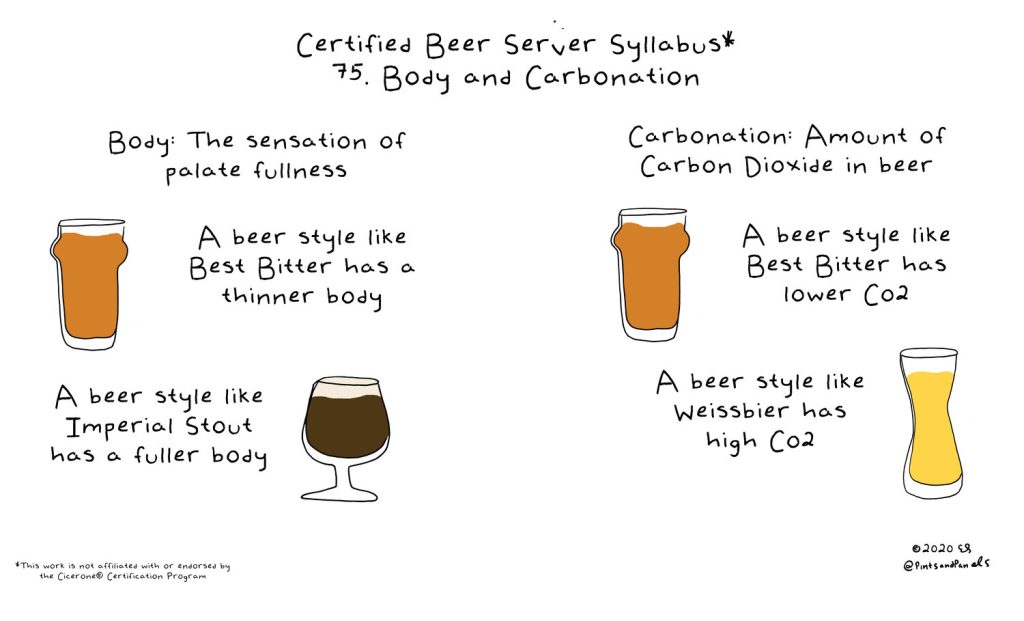

Body. In craft beer, body is the consistency or the mouthfeel or thickness of the beer. It is the sensation of weight and fullness that the beer leaves in the mouth. A beer’s body is influenced by a variety of factors, including the amount and type of malt used, the alcohol content, and the carbonation level.

Beers with a lighter body are generally perceived as refreshing and easy to drink, while beers with a heavier body are perceived as more substantial and filling. A beer’s body can be described using terms such as light, medium, full, or creamy, among others.

The body of a beer can affect the overall flavor and aroma perception. For example, a beer with a lighter body may highlight hop bitterness or a subtle malt sweetness, while a beer with a heavier body may emphasize the rich, malt flavors and provide a warming sensation from the alcohol content.

Achieving the desired body in a beer requires careful attention to the brewing process. Factors such as the mash temperature, yeast selection, and carbonation level can all impact the final body of the beer. Brewers may also use adjuncts such as oats, wheat, or lactose to increase the body of a beer, or they may use techniques such as decoction mashing to create a fuller body.

In general, a beer’s body should be balanced with its other characteristics such as flavor, aroma, and bitterness to create a well-rounded and enjoyable drinking experience.

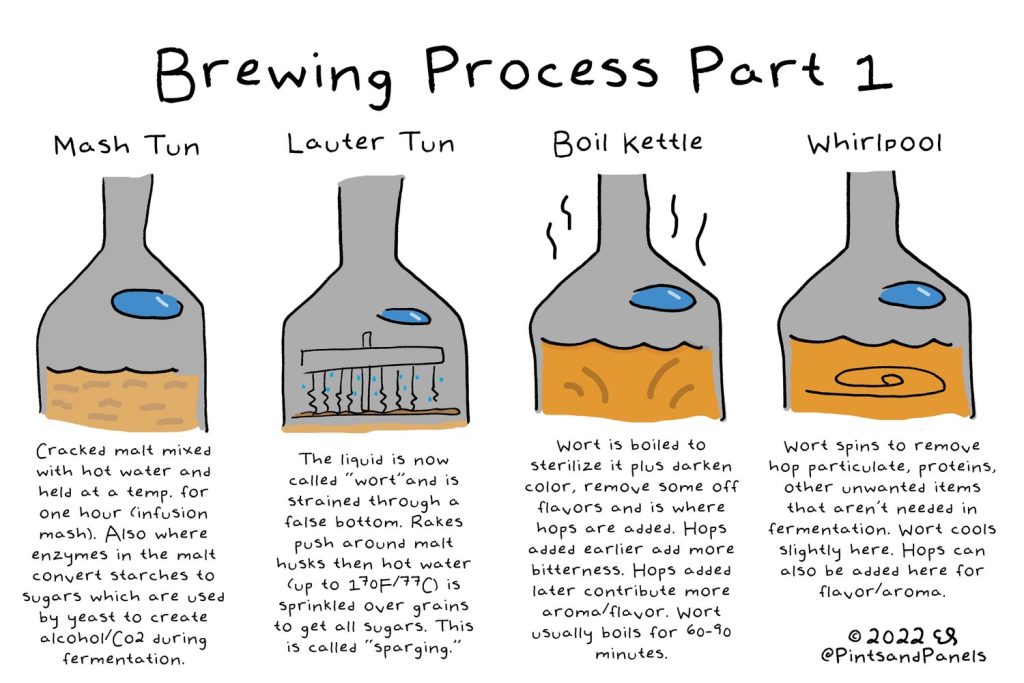

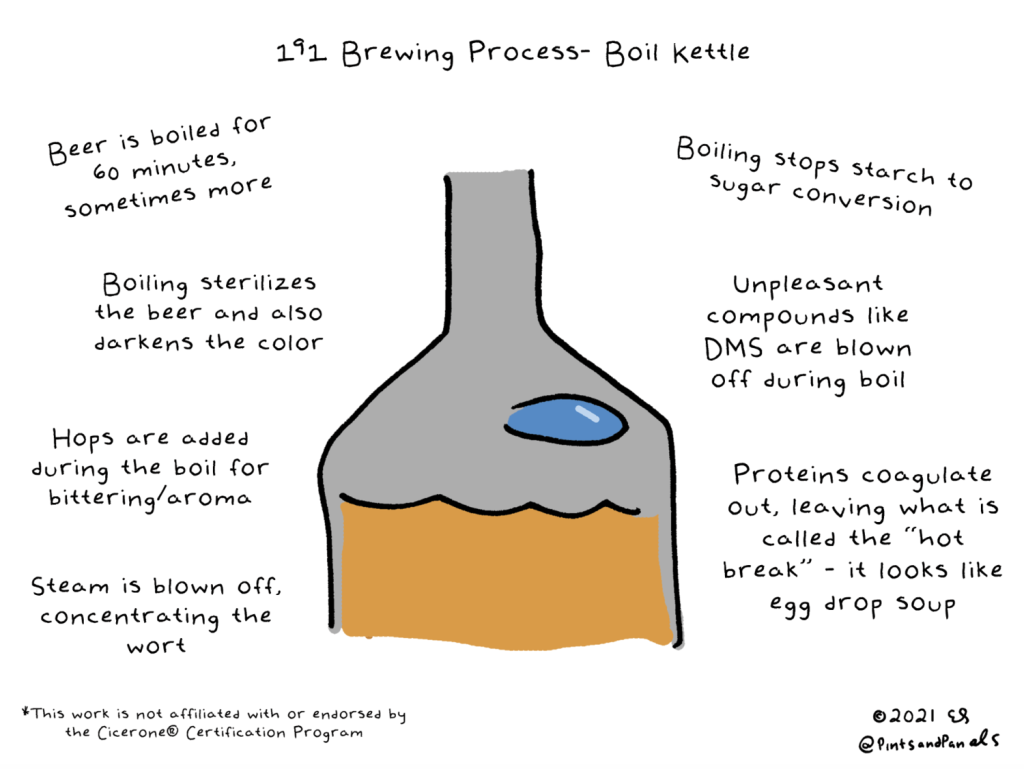

Boiling is an essential step in the brewing process of craft beer, where the wort (unfermented beer) is boiled to extract bitterness, flavor, and aroma from the hops, sterilize the wort, and concentrate the sugars in the wort to achieve the desired original gravity (OG) of the beer.

Boiling is an essential step in the brewing process of craft beer, where the wort (unfermented beer) is boiled to extract bitterness, flavor, and aroma from the hops, sterilize the wort, and concentrate the sugars in the wort to achieve the desired original gravity (OG) of the beer.

During boiling, hops are added at various times to extract different flavors and aromas. Early hop additions contribute bitterness to the beer, while later additions add flavor and aroma. Boiling also drives off volatile compounds and undesirable flavors from the wort, which contributes to the overall cleanliness and stability of the finished beer.

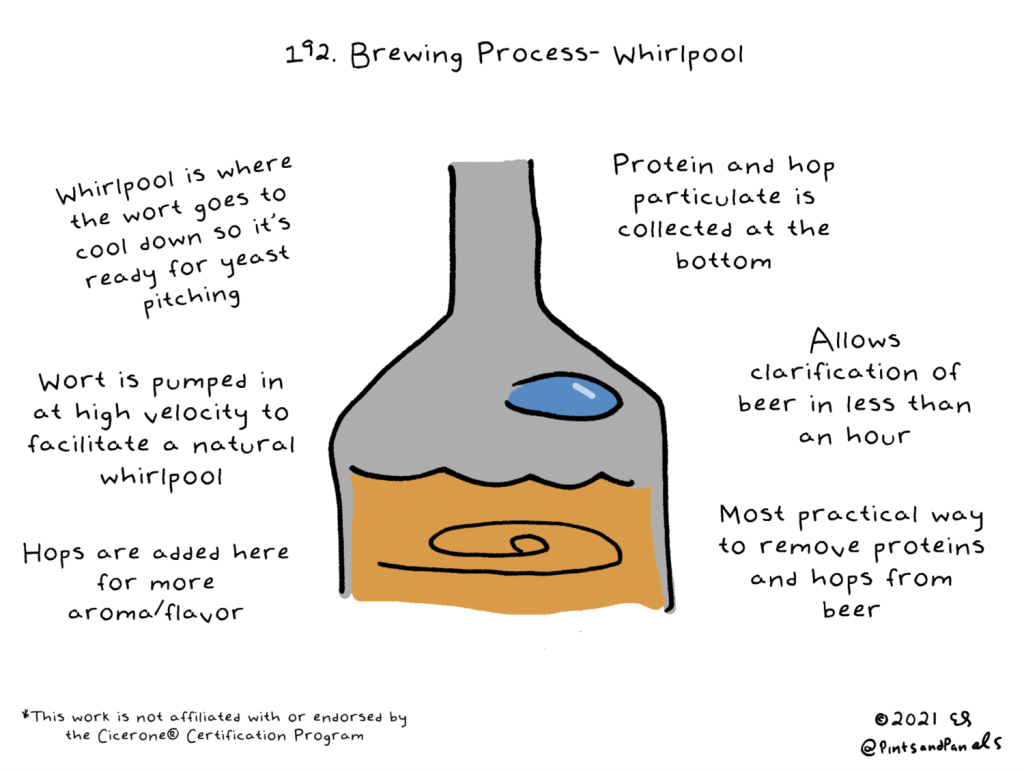

Boiling times can range from 30 minutes to several hours depending on the beer style and the desired flavor profile. The boiling process also helps to coagulate and precipitate proteins and other solids from the wort, which can be removed through the whirlpool or during fermentation.

In addition to hop additions, brewers may add adjuncts such as fruit, spices, or other flavorings during the boil to create unique and complex flavor profiles in the finished beer.

After boiling, the wort is rapidly cooled to a temperature suitable for yeast fermentation. The boiled wort is then transferred to a fermentation vessel where yeast is added to ferment the sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide, ultimately creating the finished craft beer.

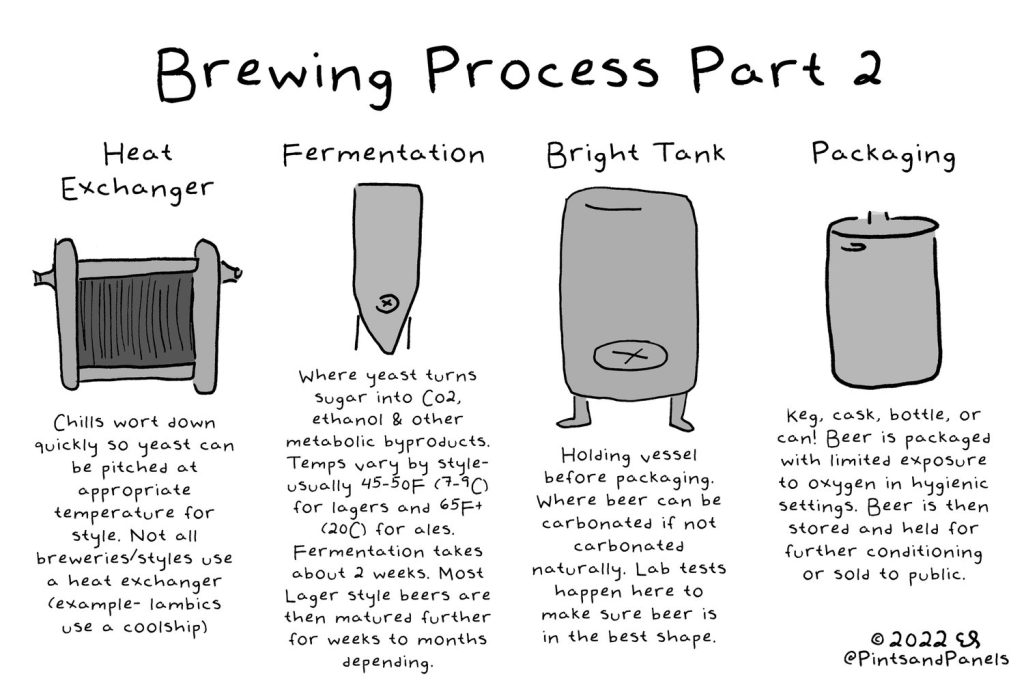

Bottle Conditioning in craft beer refers to the process of adding a small amount of fermentable sugar and yeast to the beer before bottling, allowing the beer to undergo a secondary fermentation in the bottle. This process creates natural carbonation and can enhance the complexity and flavor of the beer.

After primary fermentation is complete, the beer is typically transferred to a secondary vessel where additional flavors may be added, such as dry hops or fruit. At this point, a small amount of yeast and sugar is added to the beer before it is bottled. The yeast consumes the added sugar, creating carbon dioxide, which is trapped in the bottle, resulting in carbonation.

The beer is then left to condition in the bottle for several weeks or months, allowing the yeast to work its magic and contribute to the beer’s flavor and aroma. The yeast can also help to clarify the beer by consuming any residual sugars or unwanted compounds, resulting in a clear and bright final product.

Bottle conditioning is a traditional technique that has been used for centuries in brewing, and it is still widely used in craft beer today. It can add complexity, depth, and a unique character to the beer that cannot be achieved through other methods of carbonation, such as forced carbonation.

While bottle conditioning can result in a more complex and flavorful beer, it also requires careful attention to sanitation and storage conditions to avoid off flavors or spoilage. Craft beer drinkers often seek out bottle-conditioned beers for their unique character and natural carbonation.

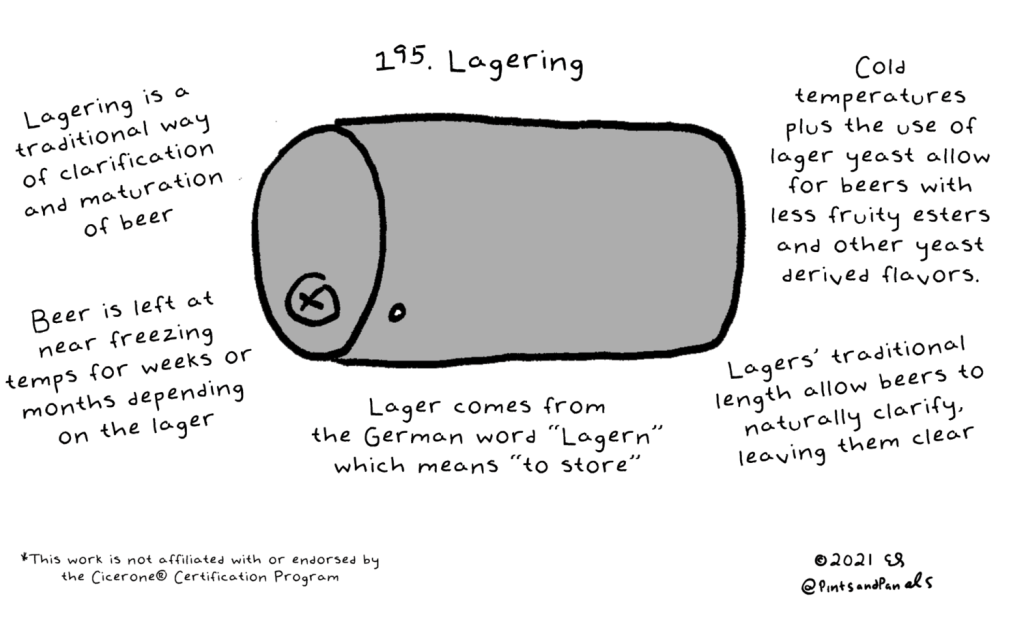

Bottom fermentation, also known as lagering, is a method of fermentation used in the production of certain styles of craft beer, such as lagers and pilsners. It is called bottom fermentation because the yeast used in this process sinks to the bottom of the fermentation vessel.

During bottom fermentation, the yeast is typically fermented at lower temperatures, around 7-13°C (45-55°F), which slows down the fermentation process and results in a cleaner, crisper beer with a lighter body. The yeast used in bottom fermentation is also a different strain of yeast than those used in top fermentation, which is used to produce ales.

After primary fermentation is complete, the beer is typically conditioned at near-freezing temperatures for several weeks to several months. This is known as lagering, which allows the beer to mature and develop its unique flavor profile. The cold temperatures also help to clarify the beer by causing proteins and other compounds to settle out of the beer.

Bottom-fermented beers tend to have a clean, crisp flavor profile, with a moderate hop bitterness and a smooth, easy-drinking character. They are also typically lighter in body and color than top-fermented beers. Some examples of bottom-fermented beer styles include pilsners, bocks, and dunkels.

Overall, bottom fermentation is a key process in the production of many popular beer styles, and it requires careful attention to temperature control and fermentation conditions to achieve the desired flavor and aroma profile.

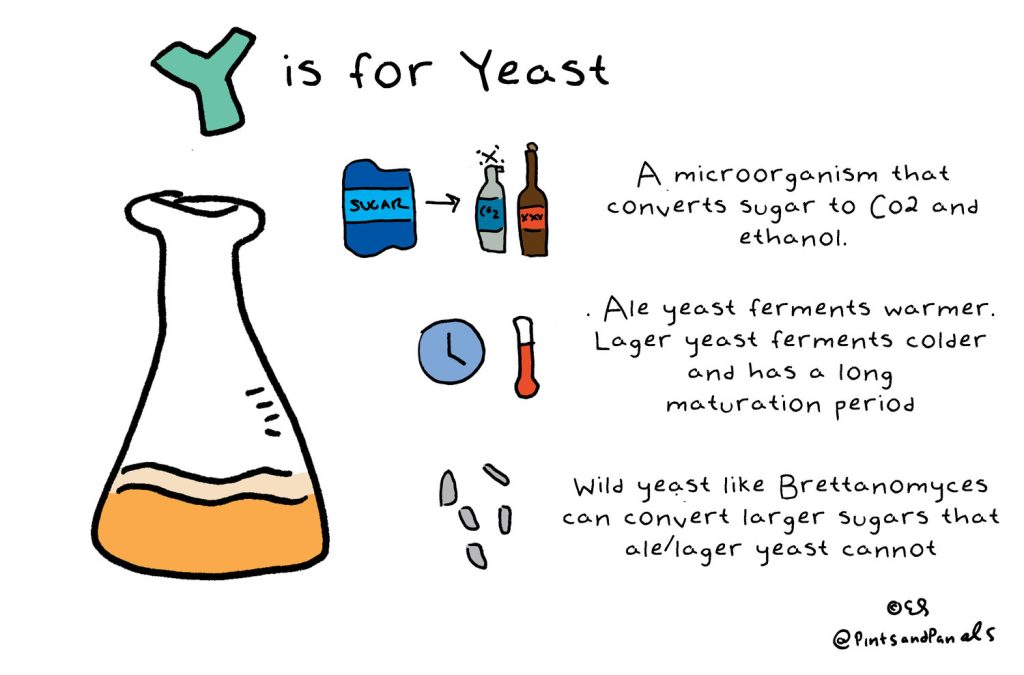

Brettanomyces, often referred to as “Brett” for short, is a type of wild yeast that is commonly used in the production of craft beer. Brettanomyces is known for its ability to ferment sugars that other yeast strains cannot, resulting in unique flavor and aroma profiles.

Brettanomyces is commonly used in the production of sour beers, which are brewed using wild yeast and bacteria to produce tart, funky flavors and aromas. Brettanomyces can also be used to add complexity and depth to other beer styles, such as IPAs and saisons.

Beers fermented with Brettanomyces can exhibit a wide range of flavor and aroma profiles, including fruity, earthy, barnyard, and even leather-like notes. The exact flavor and aroma profile will depend on the specific strain of Brettanomyces used, as well as the brewing techniques and ingredients used in the beer.

While Brettanomyces is prized for the unique flavors and aromas it can contribute to beer, it can also be a difficult yeast to work with, as it can be slow to ferment and can be difficult to control. Additionally, Brettanomyces can be a resilient yeast that can persist in brewing equipment and can contaminate subsequent batches of beer if proper sanitation practices are not followed.

Overall, Brettanomyces is a key ingredient in the production of many popular styles of craft beer, and it is prized for the complex and unique flavors it can contribute to beer.

The Brewers Association (BA) is a non-profit trade organization based in the United States that represents small and independent craft breweries. The organization was founded in 2005 through the merger of two other brewing organizations, the Association of Brewers and the Brewers’ Association of America.

The Brewers Association (BA) is a non-profit trade organization based in the United States that represents small and independent craft breweries. The organization was founded in 2005 through the merger of two other brewing organizations, the Association of Brewers and the Brewers’ Association of America.

The Brewers Association’s mission is to promote and protect independent craft breweries and the community of enthusiasts that surround them. The organization provides a wide range of services and resources to its members, including advocacy and lobbying efforts, industry research, educational programs, and marketing and promotional support.

One of the most well-known initiatives of the Brewers Association is the “Independent Craft Brewer Seal,” which is a seal that can be displayed on beer packaging and taproom signage to indicate that the beer is produced by an independent craft brewery. The seal was introduced in 2017 as a way to help consumers differentiate between independent craft breweries and those owned by larger corporations.

In addition to its advocacy efforts, the Brewers Association is also responsible for organizing several large-scale beer festivals, including the Great American Beer Festival, which is one of the largest beer festivals in the world. The organization also publishes a variety of industry-related publications, including the BA’s official magazine, The New Brewer.

Overall, the Brewers Association plays a significant role in the craft beer industry in the United States, serving as a voice and resource for small and independent breweries and helping to promote and protect the culture of craft beer.

Brew Kettle, also known as a boiling kettle, is a vessel used in the brewing process to boil the wort, a liquid extracted from malted barley and other grains, with hops to add flavor and bitterness to the beer.

The brew kettle is typically made of stainless steel or copper and is heated by either direct fire or steam. During the boiling process, the wort is sterilized and any unwanted flavors and aromas are eliminated. The hops are added at different times during the boil to achieve various levels of bitterness, flavor, and aroma.

After boiling, the wort is usually cooled and transferred to a fermenter where yeast is added to begin the fermentation process. The brew kettle is an essential piece of equipment in the brewing process and plays a crucial role in the final flavor and quality of the beer.

Bung. A bung is a stopper that is used to seal the opening of a cask or barrel. The bung is typically made of wood, cork, or rubber and is designed to fit snugly into the opening of the container to prevent any air from getting inside.

Bungs are important in the brewing process because they help to maintain the quality and freshness of the beer by preventing oxidation and contamination. Once the beer has finished fermenting, it is often transferred to a cask or barrel for conditioning and maturation. The bung is then inserted into the opening of the cask or barrel to seal it tightly.

During the conditioning process, the beer will continue to ferment slowly and develop its flavor and character. The bung may need to be removed periodically to allow excess gas to escape, but it must be replaced quickly to prevent any air from entering the cask or barrel.

In addition to their use in casks and barrels, bungs are also used to seal the openings of fermentation vessels, such as fermenting buckets and carboys.

C

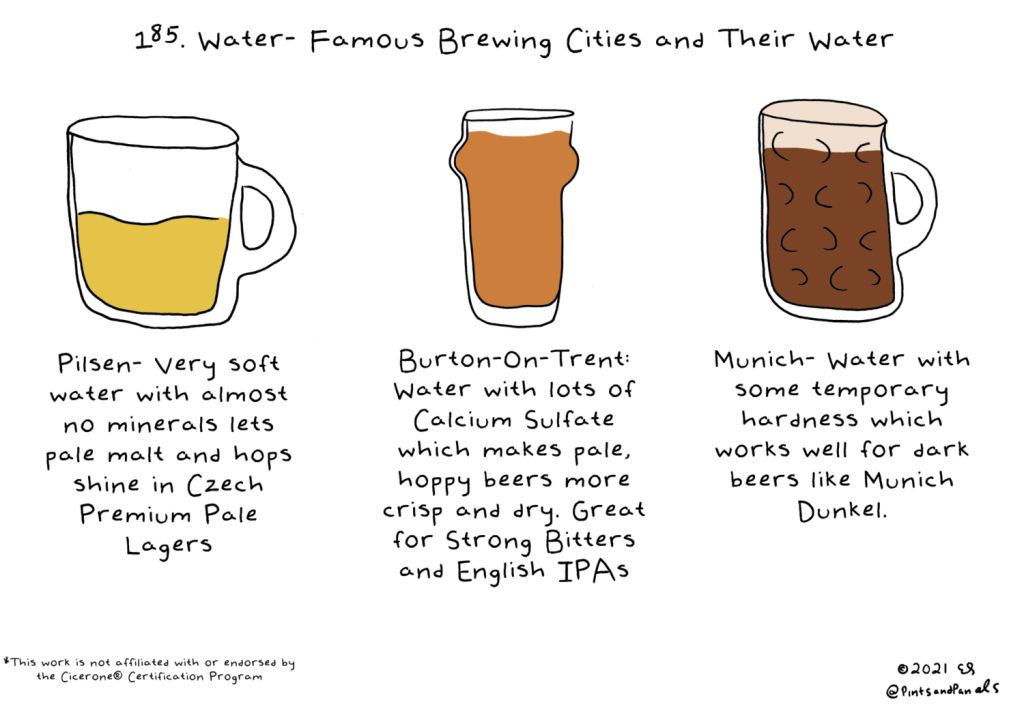

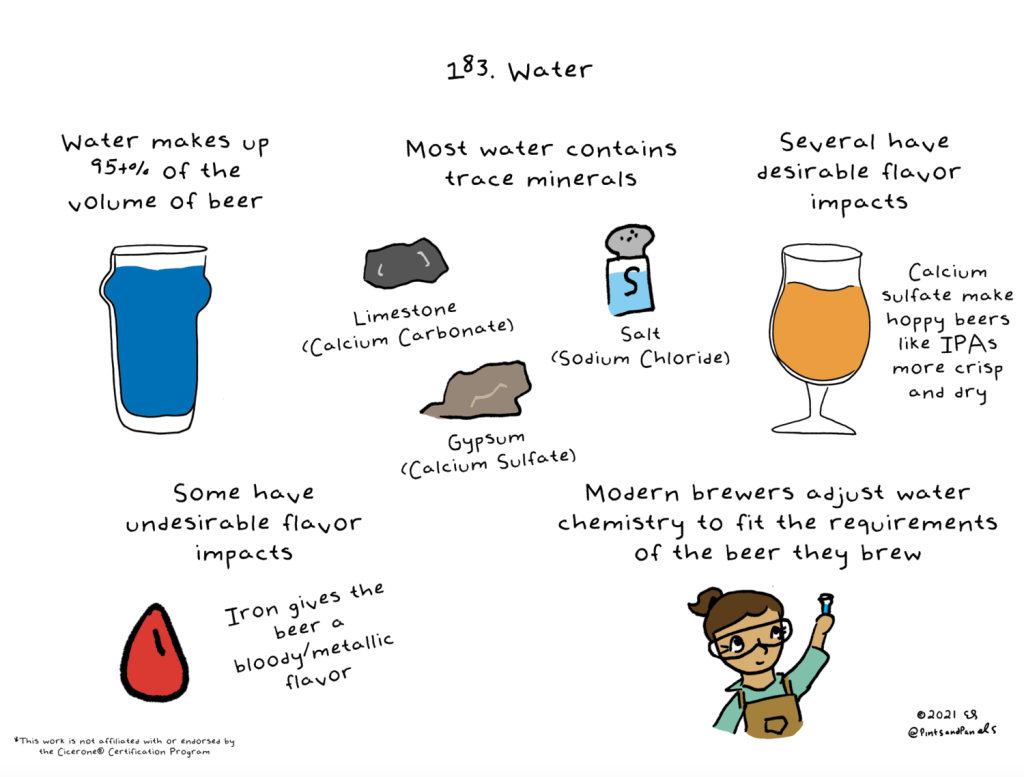

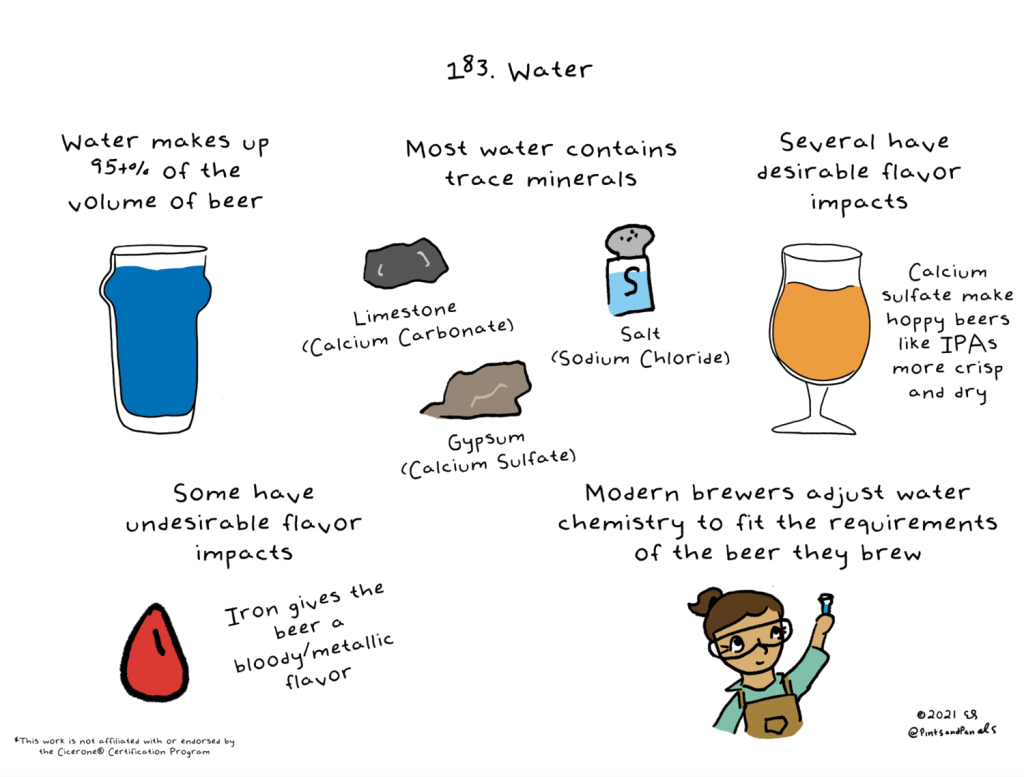

Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) also known as chalk, is a chemical compound that is commonly used in craft brewing to adjust the pH level of the brewing water.

Water chemistry is an important aspect of brewing, as it affects the flavor, aroma, and quality of the finished beer. In some regions, the water has a naturally high pH, which can lead to off-flavors and cloudiness in the beer. By adding calcium carbonate to the water, brewers can increase the alkalinity and raise the pH level to the optimal range for brewing.

Calcium carbonate is also a source of calcium ions, which are essential for yeast health and fermentation. Yeast requires calcium for cell membrane formation and enzyme activity, and a lack of calcium can lead to slow or incomplete fermentation.

Calcium carbonate can be added directly to the brewing water or in the mash, depending on the specific recipe and desired pH level. It is important to measure the pH level of the water throughout the brewing process to ensure that it stays within the optimal range for the beer style being brewed.

Calcium Sulfate (CaSO4) also known as gypsum, is a common mineral that is often used in craft beer brewing to adjust the calcium and sulfate levels of the brewing water.

Water chemistry plays a critical role in the brewing process, and the mineral content of the water can affect the flavor, aroma, and quality of the finished beer. Calcium sulfate is added to the brewing water to increase the calcium and sulfate levels, which can enhance the hop bitterness and improve the clarity and mouthfeel of the beer.

In particular, calcium sulfate is known for its ability to enhance the hop bitterness in beer. This is because sulfate ions are important for hop flavor and aroma, and increasing the sulfate levels in the water can intensify the bitterness and add a crisp, dry finish to the beer. The calcium ions from calcium sulfate also help to lower the pH of the mash, which can improve the enzyme activity and fermentability of the wort.

Calcium sulfate can be added directly to the brewing water, typically during the mashing process. It is important to measure the mineral content of the water throughout the brewing process to ensure that it stays within the optimal range for the beer style being brewed.

Carbohydrates are a class of organic compounds that are composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. In brewing, carbohydrates play an important role as they are the primary source of fermentable sugars that yeast use to produce alcohol and carbon dioxide during fermentation.

The most common carbohydrate used in craft beer brewing is maltose, which is a disaccharide composed of two glucose molecules. Maltose is created during the mashing process when enzymes in the malted grains break down the complex starches into simpler sugars. Other fermentable sugars in beer may include glucose, fructose, and sucrose.

During fermentation, yeast consume the fermentable sugars and convert them into alcohol and carbon dioxide. The type and amount of carbohydrates used in the brewing process can affect the flavor, body, and alcohol content of the finished beer. For example, using more complex carbohydrates like dextrins can create a fuller body and a sweeter, maltier flavor in the beer, while using simpler sugars can result in a lighter body and a drier finish.

Carbohydrates can also be used in beer brewing as adjuncts to increase the fermentable sugar content and improve the mouthfeel and flavor of the beer. Examples of commonly used adjuncts include corn, rice, and wheat, which can provide fermentable sugars and contribute to the overall flavor profile of the beer.

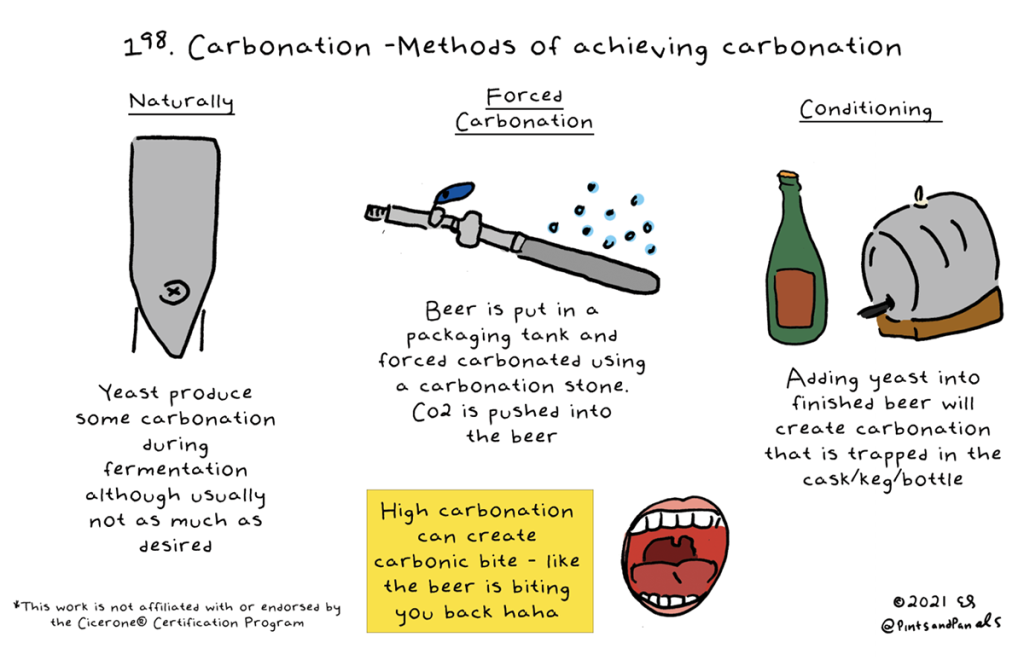

Carbon Dioxide (CO2) is a naturally occurring gas that is used in craft beer brewing to carbonate and condition the beer.

During the fermentation process, yeast consumes fermentable sugars and produces alcohol and carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide produced during fermentation is dissolved into the beer, creating a natural level of carbonation. However, this level of carbonation may not be sufficient for certain beer styles or desired carbonation levels.

To increase carbonation, brewers often add additional carbon dioxide to the beer during packaging. This is typically done by force carbonation, where carbon dioxide gas is pressurized into the beer at a specific temperature and pressure to achieve the desired level of carbonation. Alternatively, brewers can add a small amount of sugar or wort to the beer prior to bottling or kegging, which creates additional carbon dioxide during a secondary fermentation in the bottle or keg.

Carbon dioxide can also be used during the brewing process to purge or flush oxygen from equipment and tanks to prevent oxidation and off-flavors in the beer. It can also be used to push beer through keg lines or serve tanks to maintain carbonation and dispense the beer.

Carbonation is the process of dissolving carbon dioxide (CO2) gas into beer to create carbonation or bubbles in the liquid. The process of carbonation in craft beer brewing can occur naturally during fermentation or can be achieved through artificial means.

Naturally Carbonated Beer:

During fermentation, yeast consumes fermentable sugars and produces alcohol and carbon dioxide. As the carbon dioxide is produced, it dissolves into the beer and creates a natural level of carbonation. This is known as bottle conditioning or secondary fermentation, where a small amount of sugar is added to the beer prior to bottling or kegging, which creates additional carbon dioxide during a secondary fermentation in the bottle or keg. This creates a natural, fine carbonation with small bubbles in the beer, resulting in a smooth mouthfeel.

Artificially Carbonated Beer:

Many craft beers are artificially carbonated using pressurized carbon dioxide gas. This process is typically done by force carbonation, where carbon dioxide gas is pressurized into the beer at a specific temperature and pressure to achieve the desired level of carbonation. The beer is typically chilled and then pressurized in a sealed tank with carbon dioxide until it reaches the desired level of carbonation. The carbonation levels are carefully controlled to ensure consistency across batches.

Overall, the process of carbonation in craft beer brewing is critical to the flavor, aroma, and mouthfeel of the beer. The level of carbonation can affect the perception of sweetness, bitterness, and acidity in the beer, as well as the aroma and texture. Carbonation can also play a role in the stability and shelf life of the beer, as it can help to prevent oxidation and other off-flavors from developing over time.

Carboy is a type of container used for fermenting and aging beer. It is typically made of glass or plastic and has a narrow neck and a wide body. Carboys are often preferred by home brewers and small-scale craft breweries because they are easy to clean and sanitize, and they allow for better observation of the fermentation process.

Carboys come in different sizes, ranging from one gallon to six gallons or more. They are usually fitted with an airlock, which allows carbon dioxide to escape during the fermentation process while preventing oxygen from entering the container and potentially spoiling the beer.

Overall, carboys are an essential piece of equipment for any home brewer or small craft brewery looking to produce high-quality beer.

Caryophyllene is a natural compound found in many plants, including hops. In craft beer, caryophyllene is often associated with the spicy, earthy, and herbal aromas and flavors that are characteristic of certain hop varieties.

Caryophyllene is one of the major components of the essential oils found in hops, along with other compounds like myrcene and humulene. It is also known for its potential health benefits, including anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in using hop varieties that are high in caryophyllene to create unique and flavorful craft beers. Some breweries even use caryophyllene-rich hops as a way to differentiate their beers and appeal to health-conscious consumers.

Overall, caryophyllene is an important component of the complex flavor and aroma profile of many craft beers, particularly those that use hops as a key ingredient.

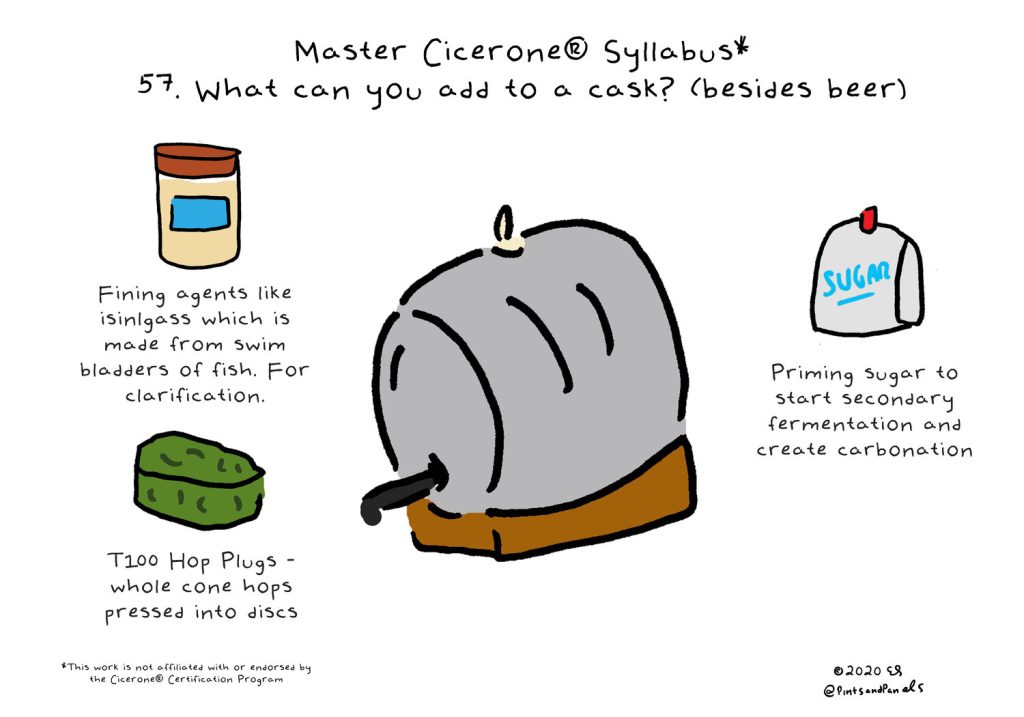

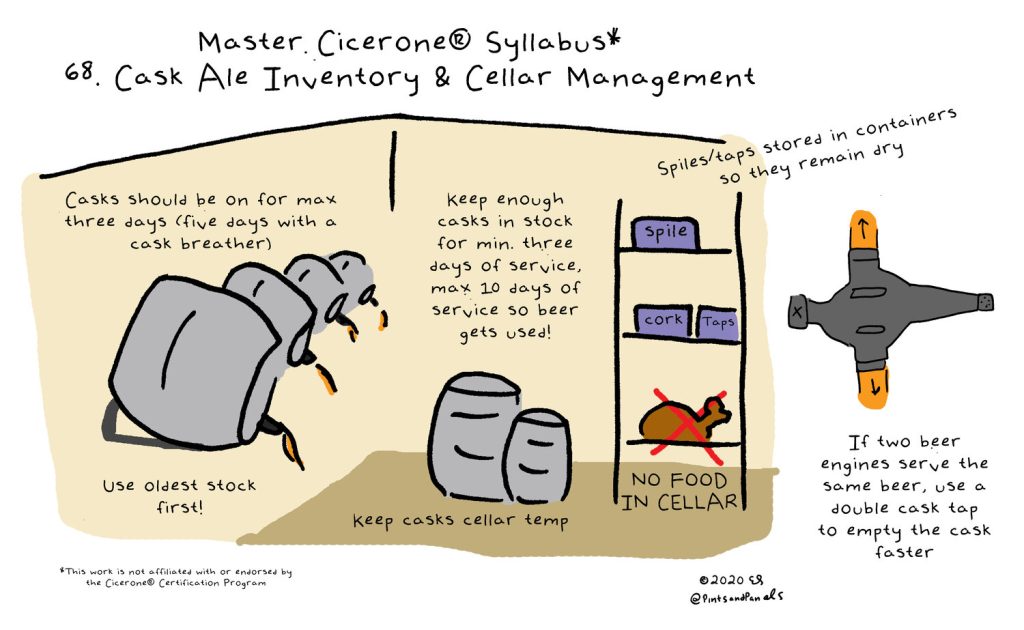

Cask. A barrel-shaped container for holding beer. Casks are typically made of metal or wood and are filled with unfiltered, unpasteurized beer that is still undergoing secondary fermentation in the container. The beer is then allowed to mature and condition naturally in the cask, often with additional hops or other ingredients added to enhance the flavor and aroma.

When the beer is ready to be served, it is manually drawn from the cask using a hand-operated pump, known as a beer engine or handpull. This gentle method of serving allows the beer to retain more of its natural carbonation and flavor, resulting in a smoother, more complex taste and mouthfeel than beer served through a pressurized system.

Cask-conditioned beer is a popular style among craft beer enthusiasts, particularly in the UK and other parts of Europe, where it has a long history and is considered a cornerstone of traditional beer culture.

Cellaring. Storing or aging beer at a controlled temperature to allow maturing.

Chill Haze. Hazy or cloudy appearance caused when the proteins and tannins naturally found in finished beer combine upon chilling into particles large enough to reflect light or become visible.

Closed Fermentation. Fermentation under closed, anaerobic conditions to minimize risk of contamination and oxidation.

Cold Break. The flocculation of proteins and tannins during wort cooling.

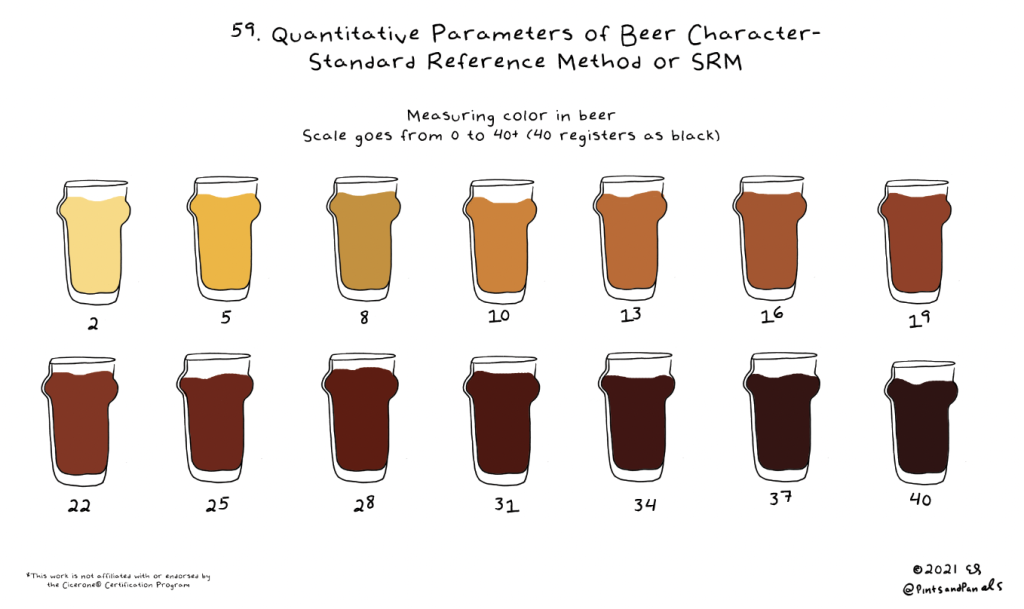

Color. The hue or shade of a beer, primarily derived from grains, sometimes derived from fruit or other ingredients in beer. Beer styles made with caramelized, toasted or roasted malts or grains will exhibit increasingly darker colors. The color of a beer may often, but not always, allow the consumer to anticipate how a beer might taste. It’s important to note that beer color does not equate to alcohol level, mouthfeel or calories in beer.

Conditioning. A step in the brewing process in which beer is matured or aged after initial fermentation to prevent the formation of unwanted flavors and compounds.

Contract Brewing Company. A business that hires another brewery to produce some or all of its beer. The contract brewing company handles marketing, sales and distribution of its beer, while generally leaving the brewing and packaging to its producer-brewery.

Craft Brewery. According to the Brewers Association, an American craft brewer is small and independent.

- Small: Annual production of 6 million barrels of beer or less (approximately 3 percent of U.S. annual sales). Beer production is attributed to a brewer according to rules of alternating proprietorships.

- Independent: Less than 25 percent of the craft brewery is owned or controlled (or equivalent economic interest) by a beverage alcohol industry member that is not itself a craft brewer.

- Brewer: Has a TTB Brewer’s Notice and makes beer.

D

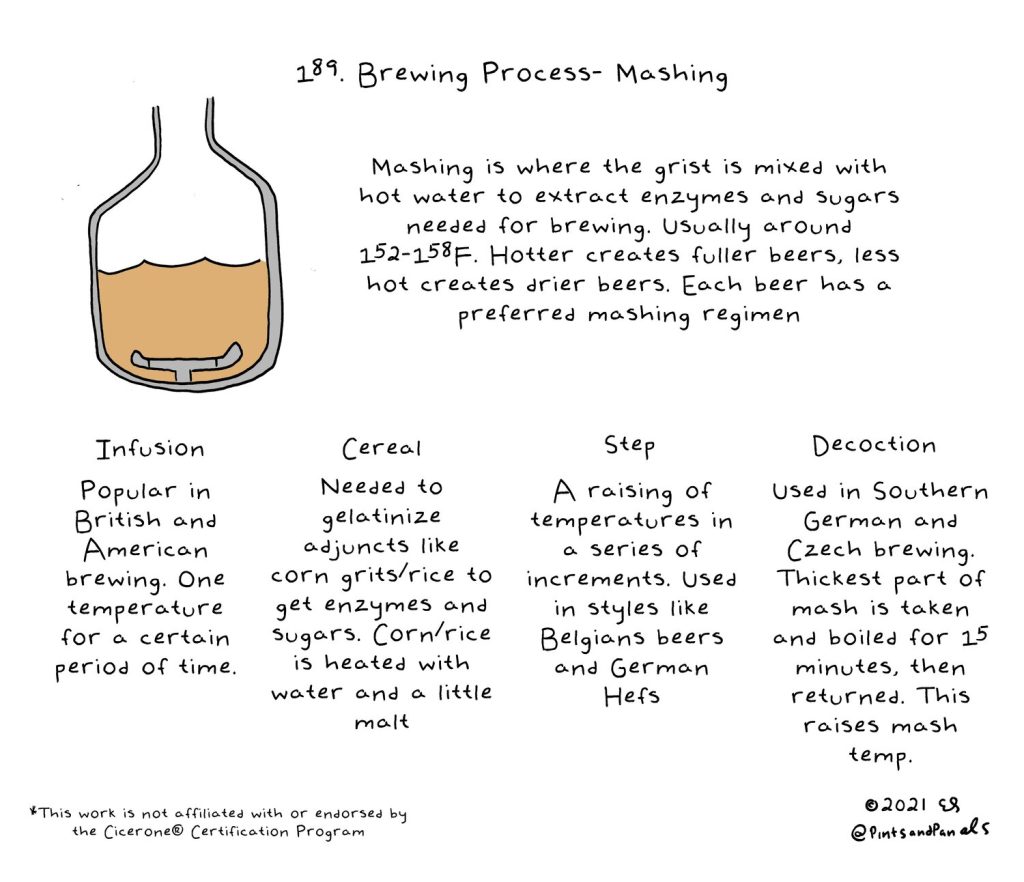

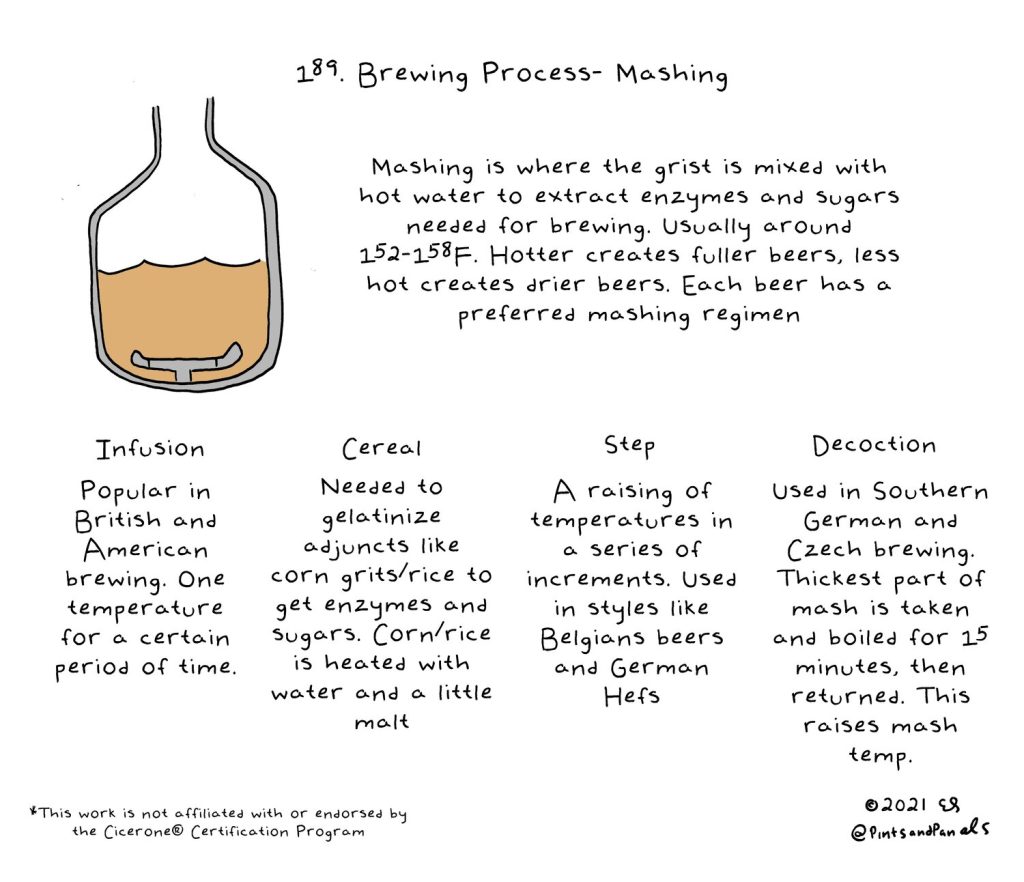

Decoction Mash. A method of mashing that raises the temperature of the mash by removing a portion, boiling it, and returning it to the mash tun. Often used multiple times in certain mash programs.

Degrees Plato. An empirically derived hydrometer scale to measure density of beer wort in terms of percentage of extract by weight.

Dextrin. A group of complex, unfermentable and tasteless carbohydrates produced by the partial hydrolysis of starch, that contributes to the gravity and body of beer. Some dextrins remain undissolved in the finished beer, giving it a malty sweetness.

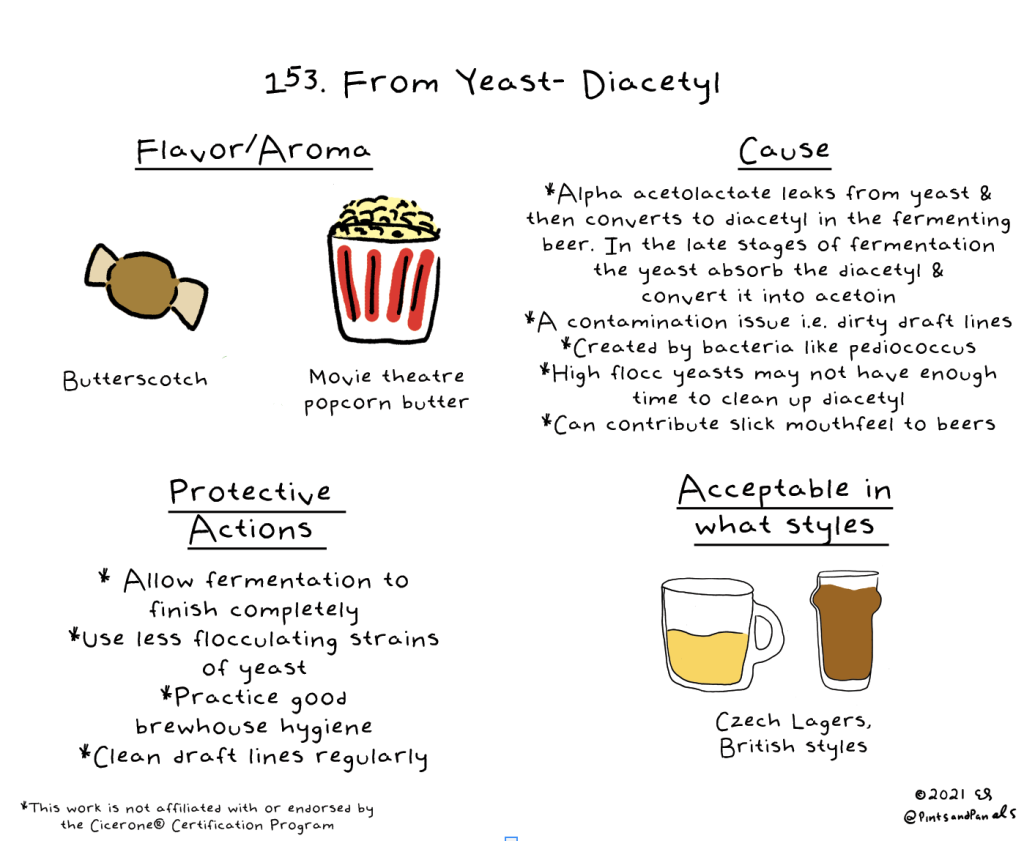

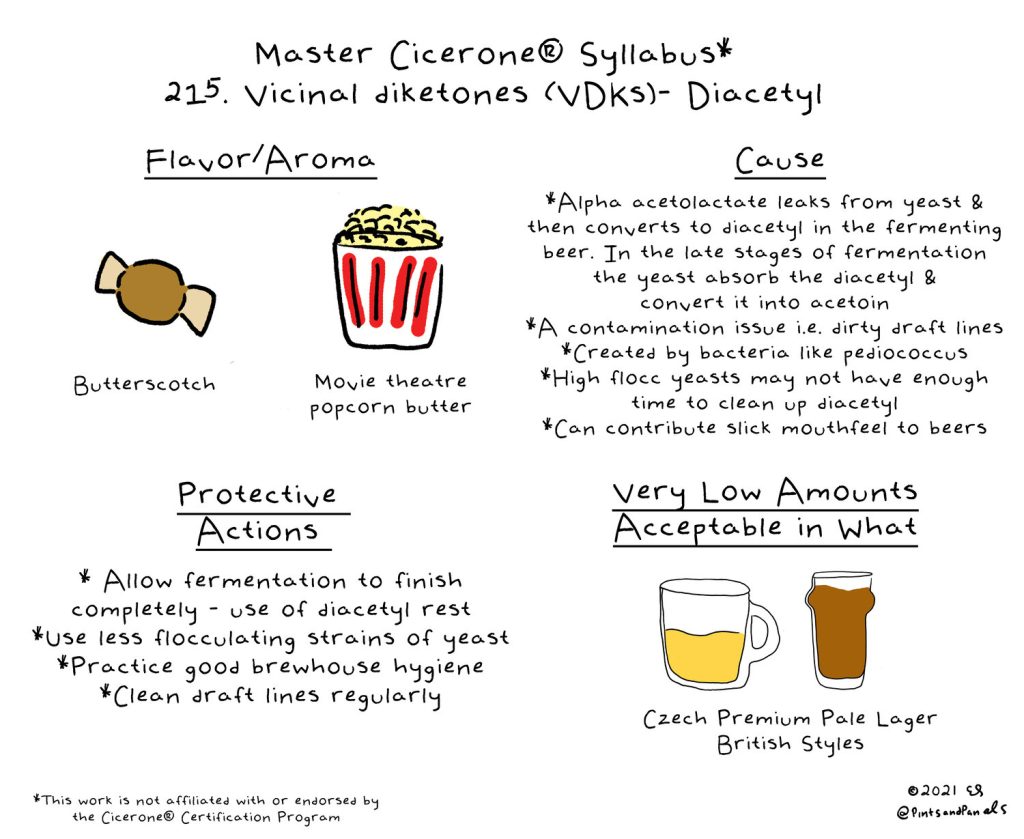

Diacetyl. A volatile compound produced by some yeasts which imparts a caramel, nutty or butterscotch flavor to beer. This compound is acceptable at low levels in several traditional beer styles, including: English and Scottish Ales, Czech Pilsners and German Oktoberfest. However, it is often an unwanted or accidental off-flavor.

Diastatic. Refers to the diastatic enzymes that are created as the grain sprouts. These convert starches to sugars, which yeast eat.

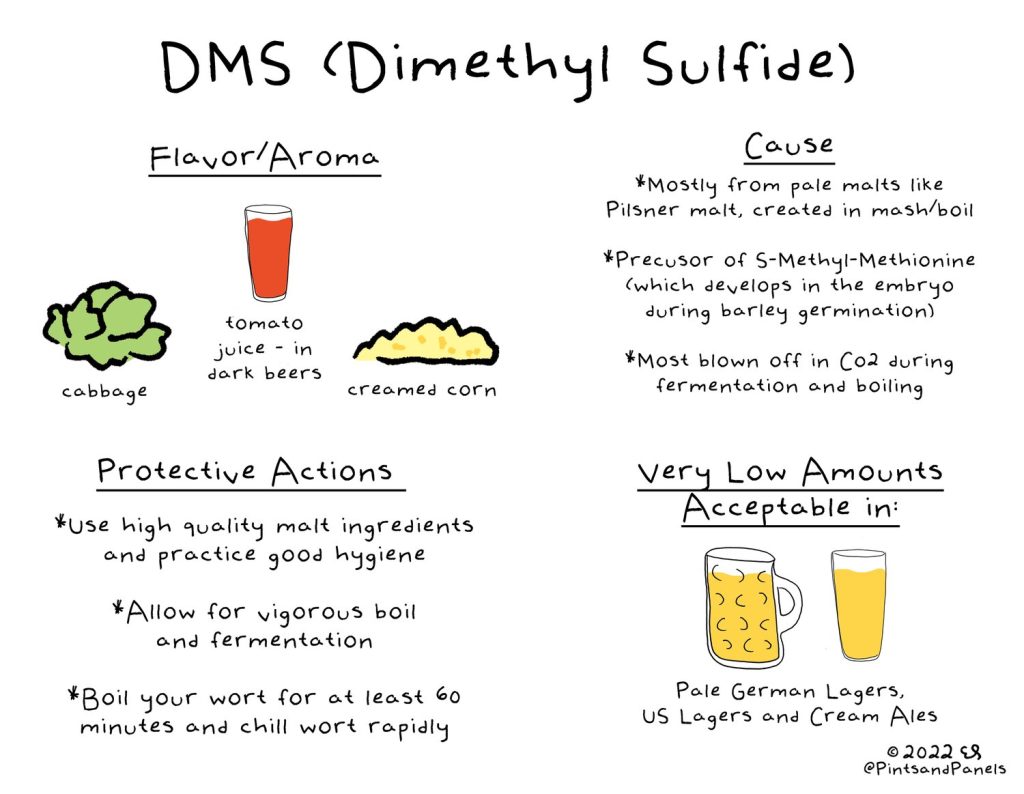

Dimethyl Sulfide (DMS). At low levels, DMS can impart a favorable sweet aroma in beer. At higher levels, DMS can impart a characteristic aroma and taste of cooked vegetables, such as cooked corn or celery. Low levels are acceptable in and characteristic of some Lager beer styles.

Draught Beer. Beer drawn from kegs, casks or serving tanks rather than from cans, bottles or other packages. Beer consumed from a growler relatively soon after filling is also sometimes considered draught beer.

Dry Hopping. The addition of hops late in the brewing process to increase the hop aroma of a finished beer without significantly affecting its bitterness. Dry hops may be added to the wort in the kettle, whirlpool, hop back, or added to beer during primary or secondary fermentation or even later in the process.

Dual Purpose Hops. Hops that are added to provide both bittering and aromatic properties.

E

Endosperm. The starch-containing sac of the barley grain.

Essential Hop Oils are what is isomerized in wort and provide the aromatic and flavor compounds that are associated with hop additions.

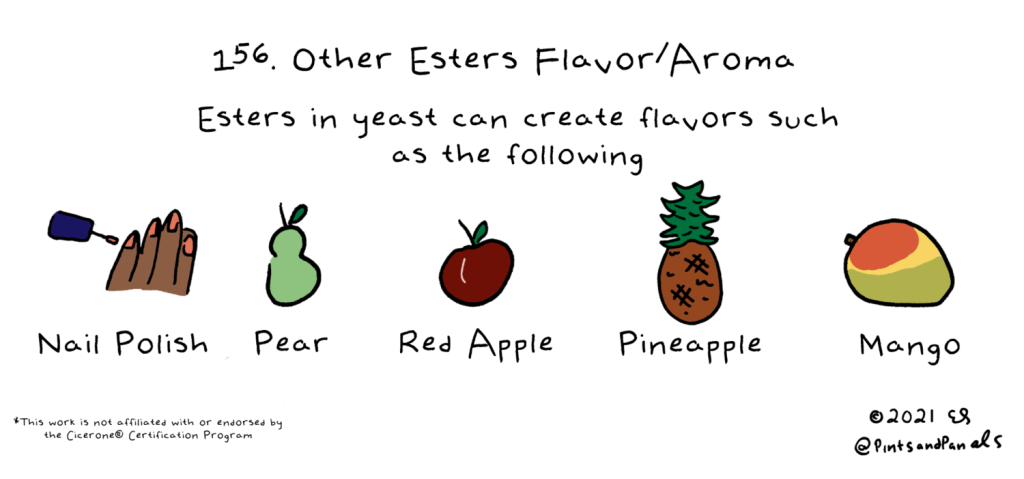

Esters. Volatile flavor compounds that form through the interaction of organic acids with alcohols during fermentation and contribute to the fruity aroma and flavor of beer. Esters are very common in ales.

Ethanol. Ethyl alcohol, the colorless primary alcohol constituent of beer.

Export. Any beer produced for the express purpose of exportation. For example: export-style German lagers or export-style Irish stouts.

F

Farnesene. One of the essential oils made in the flowering cone of the hops plant Humulus lupulus.

Fermentable Sugars. Sugars that can be consumed by yeast cells which in turn will produce ethanol alcohol and c02.

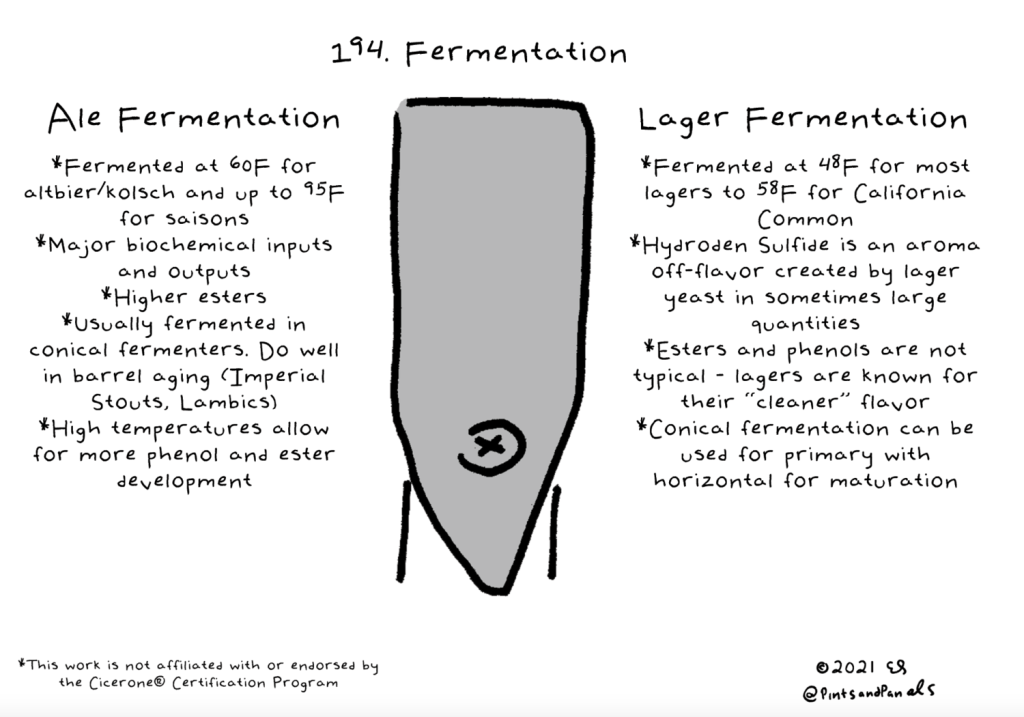

Fermentation. The chemical conversion of fermentable sugars into approximately equal parts of ethyl alcohol and carbon dioxide gas, through the action of yeast. The two basic methods of fermentation in brewing are top fermentation, which produces ales, and bottom fermentation, which produces lagers.

Fermentation Lock. A one-way valve, often made of glass or plastic that is fitted onto a fermenter and allows carbon dioxide gas to escape from the fermenter while excluding ambient wild yeasts, bacteria and contaminants.

Filtration. The passage of a liquid through a permeable or porous substance to remove solid matter in suspension, often yeast.

Final Gravity. The specific gravity of a beer as measured when fermentation is complete (when all desired fermentable sugars have been converted to alcohol and carbon dioxide gas). Synonym: Final specific gravity; final SG; finishing gravity; terminal gravity.

Fining. The process of adding clarifying agents such as isinglass, gelatin, silica gel, or Polyvinyl Polypyrrolidone (PVPP) to beer during secondary fermentation to hasten the precipitation of suspended matter, such as yeast, proteins or tannins.

Flocculation. The behavior of suspended particles in wort or beer that tend to clump together in large masses and settle out. During brewing, protein and tannin particles will flocculate out of the kettle, coolship or fermenter during hot or cold break. During and at the end of fermentation, yeast cells will flocculate to varying degrees depending on the yeast strain, thereby affecting fermentation as well as filtration of the resulting beer.

Forced Carbonation. The beer is placed into a sealed (or soon to be sealed) container and carbonation is rapidly added. Under high pressure, the CO2 is absorbed into the beer.

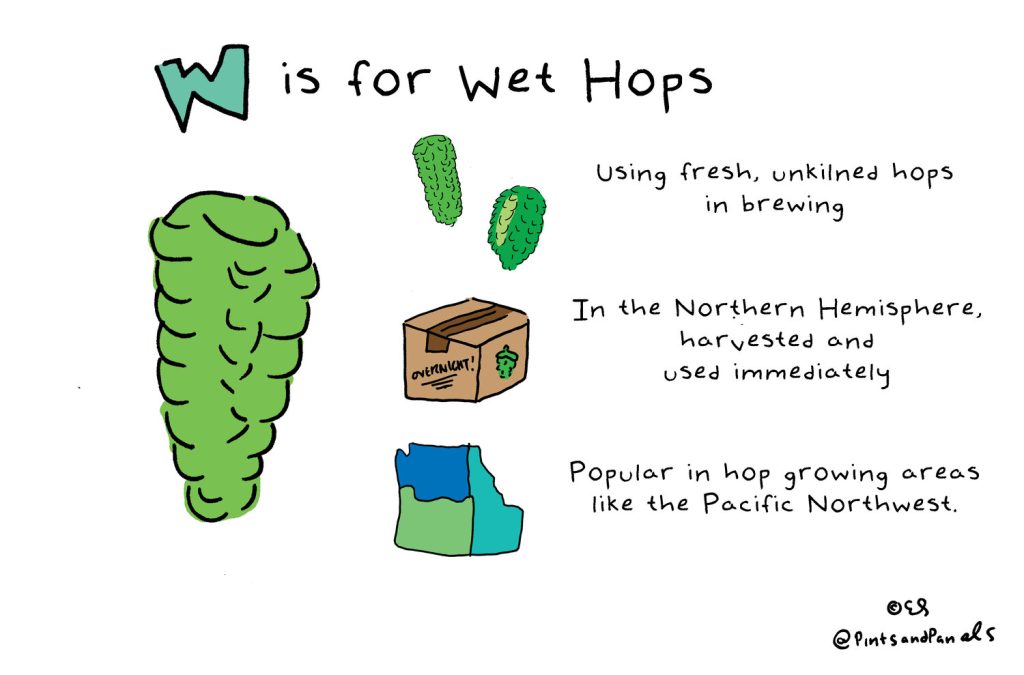

Fresh Hopping. The addition of freshly harvested hops that have not yet been dried to different stages of the brewing process. Fresh hopping adds unique flavors and aromas to beer that are not normally found when using hops that have been dried and processed per usual. Synonymous with wet hopping.

Fusel Alcohol. A family of high molecular weight alcohols, which result from excessively high fermentation temperatures. Fusel alcohols can impart harsh or solvent-like characteristics commonly described as lacquer or paint thinner. It can contribute to hangovers.

G

Germination. Growth of a barley grain as it produces a rootlet and acrospire.

Grainy. Tasting or smelling like cereal or raw grains.

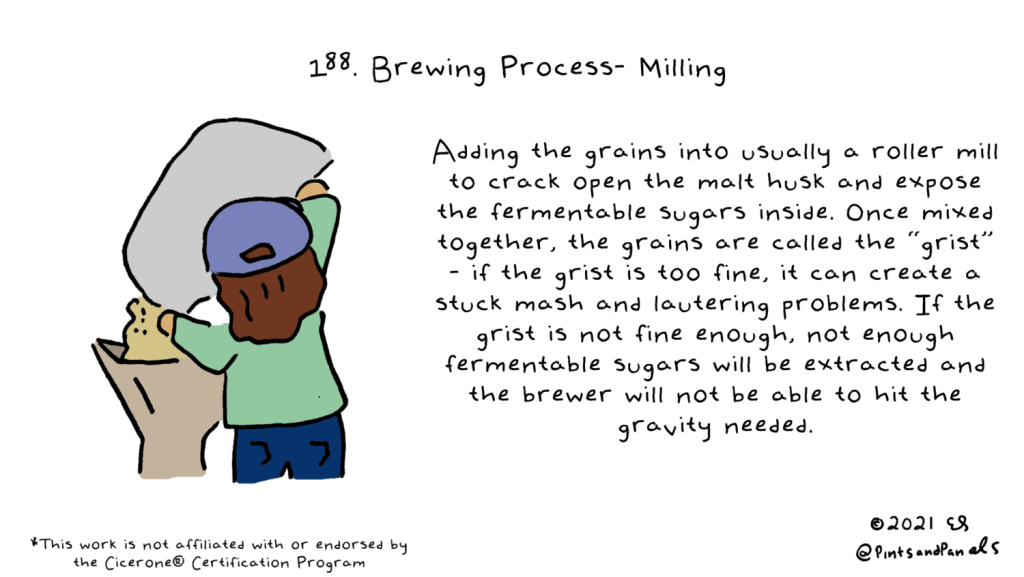

Grist. Ground malt and grains ready for mashing.

Growler. A jug- or pail-like container once used to carry draught beer bought by the measure at the local tavern. Growlers are usually ½ gal (64 oz) or 2L (68 oz) in volume and made of glass. Brewpubs often serve growlers to sell beer to-go. Often a customer will pay a deposit on the growler but can bring it back again and again for a re-fill. Growlers to-go are not legal in all U.S. states.

Gruit. An old-fashioned herb mixture used for bittering and flavoring beer, popular before the extensive use of hops. Gruit or grut ale may also refer to the beverage produced using gruit.

H

Hand Pump. A device for dispensing cask conditioned draught beer using a pump operated by hand. The use of a hand pump allows the draught beer to be served without the use of pressurized carbon dioxide.

Head Retention. The foam stability of a beer as measured, in seconds, by time required for a 1-inch foam collar to collapse.

Heat Exchangers. Used to cool hot wort before fermentation.

Homebrewing. The art of making beer at home. In the U.S., homebrewing was legalized by President Carter on February 1, 1979, through a bill introduced by California Senator Alan Cranston. The Cranston Bill allows a single person to brew up to 100 gallons of beer annually for personal enjoyment and up to 200 gallons in a household of two persons or more of legal drinking age. Learn more from the American Homebrewers Association.

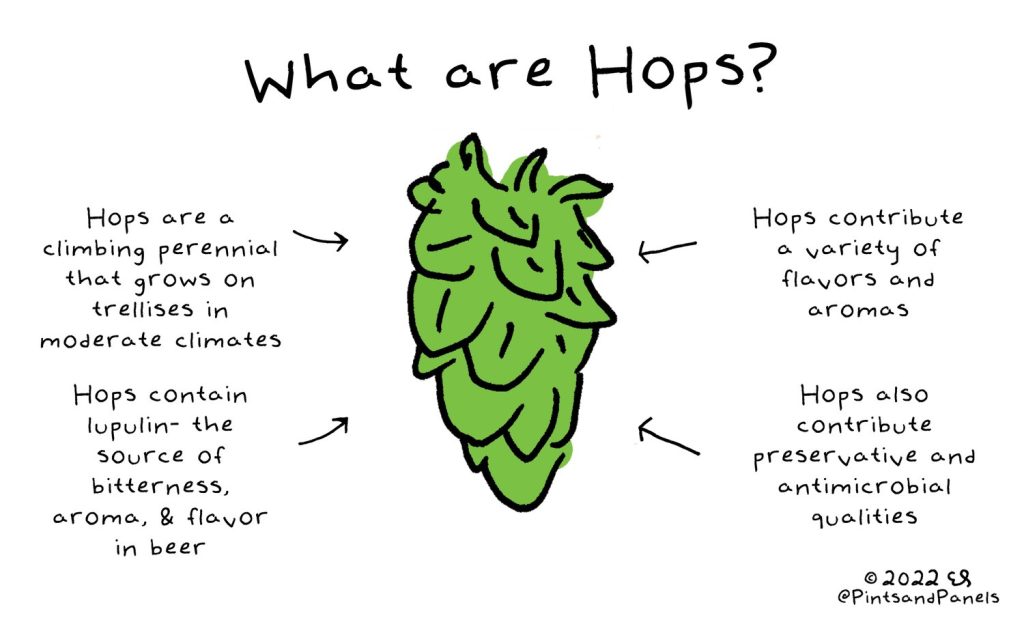

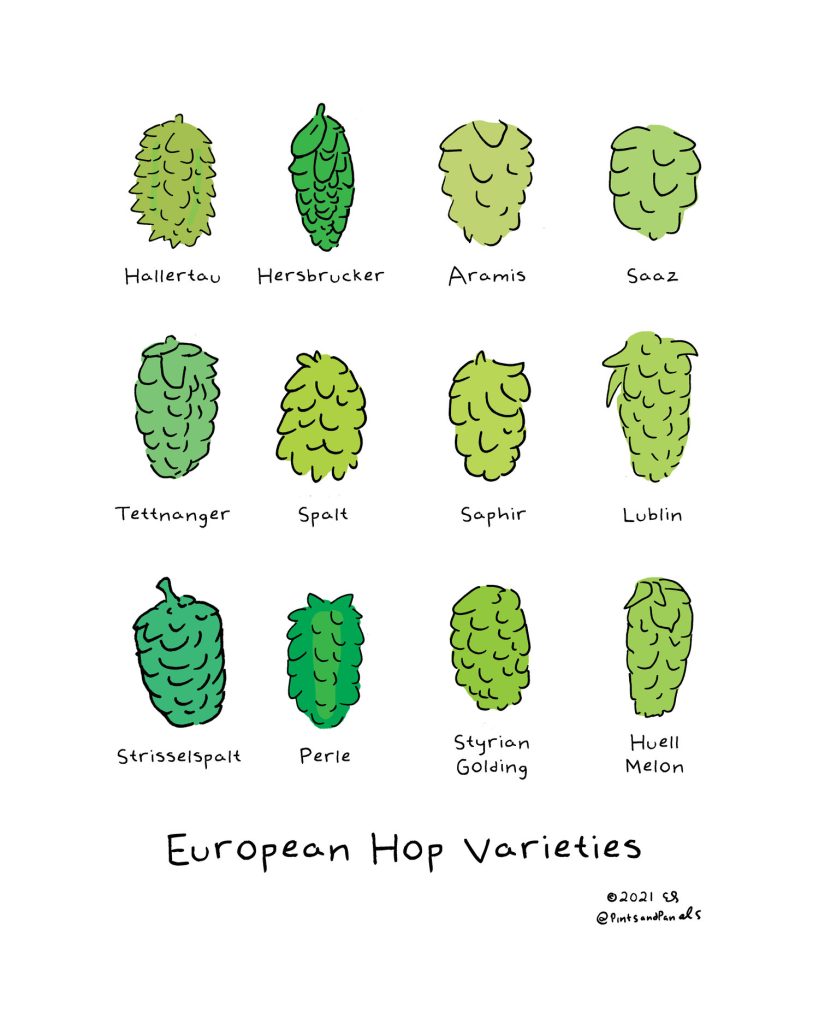

Hops. A perennial climbing bine, also known by the Latin botanical name Humulus lupulus. The female plant yields flowers of soft-leaved pine-like cones (strobile) measuring about an inch in length. Only the female ripened flower is used for flavoring beer. Because hops reproduce through cuttings, the male plants are not cultivated and are even rooted out to prevent them from fertilizing the female plants, as the cones would become weighed-down with seeds. Seedless hops have a much higher bittering power than seeded. There are presently over one hundred varieties of hops cultivated around the world. Some of the best known are Brewer’s Gold, Bullion, Cascade, Centennial, Chinook, Cluster, Comet, Eroica, Fuggles, Galena, Goldings, Hallertau, Nugget, Northern Brewer, Perle, Saaz, Syrian Goldings, Tettnang and Willamettes. Apart from contributing bitterness, hops impart aroma and flavor, and inhibit the growth of bacteria in wort and beer. Hops are added at the beginning (bittering hops), middle (flavoring hops), and end (aroma hops) of the boiling stage, or even later in the brewing process (dry hops). The addition of hops to beer dates from 7000-1000 BC; however, hops were used to flavor beer in Pharaonic Egypt around 600 BC. They were cultivated in Germany as early as AD 300 and were used extensively in French and German monasteries in medieval times and gradually superseded other herbs and spices around the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Prior to the use of hops, beer was flavored with herbs and spices such as juniper, coriander, cumin, nutmeg, oak leaves, lime blossoms, cloves, rosemary, gentian, gaussia, chamomile, and other herbs or spices.

Hopping. The addition of hops to un-fermented wort or fermented beer.

Hot Break. The flocculation of proteins and tannins during wort boiling.

Humulene. One of the essential oils made in the flowering cone of the hops plant Humulus lupulus.

Husk. The dry outer layer of certain cereal seeds.

Hydrometer. A glass instrument used to measure the specific gravity of liquids as compared to water, consisting of a graduated stem resting on a weighted float.

I

Immersion Chiller. A wort chiller most commonly made of copper that is used by submerging into hot wort before fermentation as a method of cooling.

Infusion Mash. A method of mashing which achieves target mashing temperatures by the addition of heated water at specific temperatures.

Inoculate. The introduction of a microbe such as yeast or microorganisms such as lactobacillus into surroundings capable of supporting its growth.

International Bitterness Units (IBU). The measure of the bittering substances in beer (analytically assessed as milligrams of isomerized alpha acid per liter of beer, in ppm). This measurement depends on the style of beer. Light lagers typically have an IBU rating between 5-10 while big, bitter India Pale Ales can often have an IBU rating between 50 and 70.

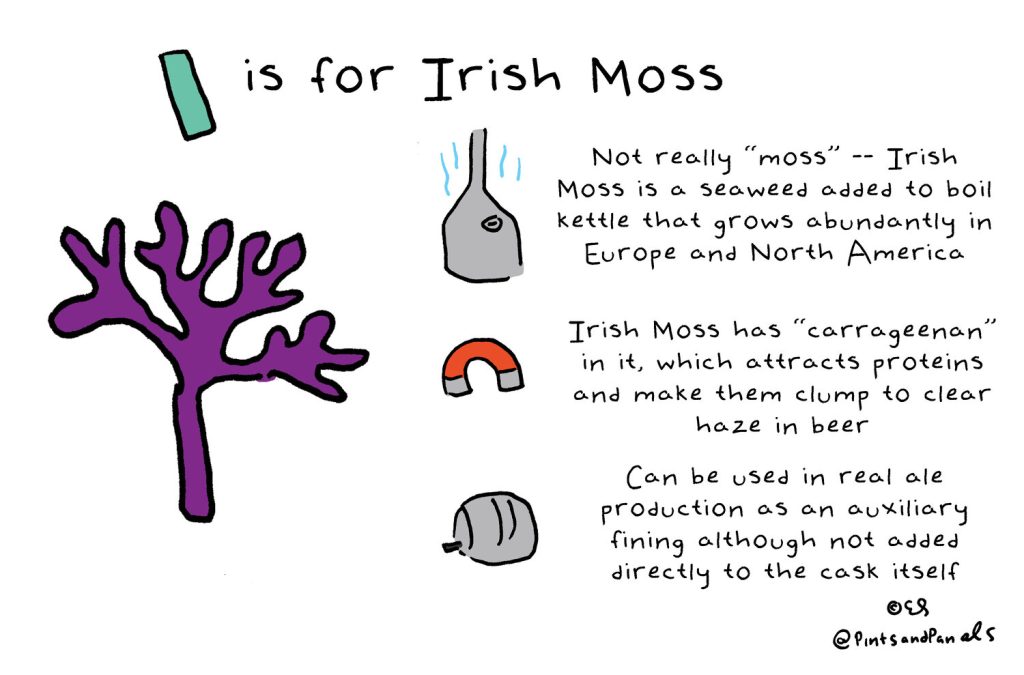

Irish Moss. Used as a clairifier in beer. Modified particles or powder of the seaweed Chondrus crispus that help to precipitate proteins in the kettle by facilitating the hot break.

Isinglass. A gelatinous substance made from the swim bladder of certain fish that is sometimes added to beer to help clarify and stabilize the finished product.

K

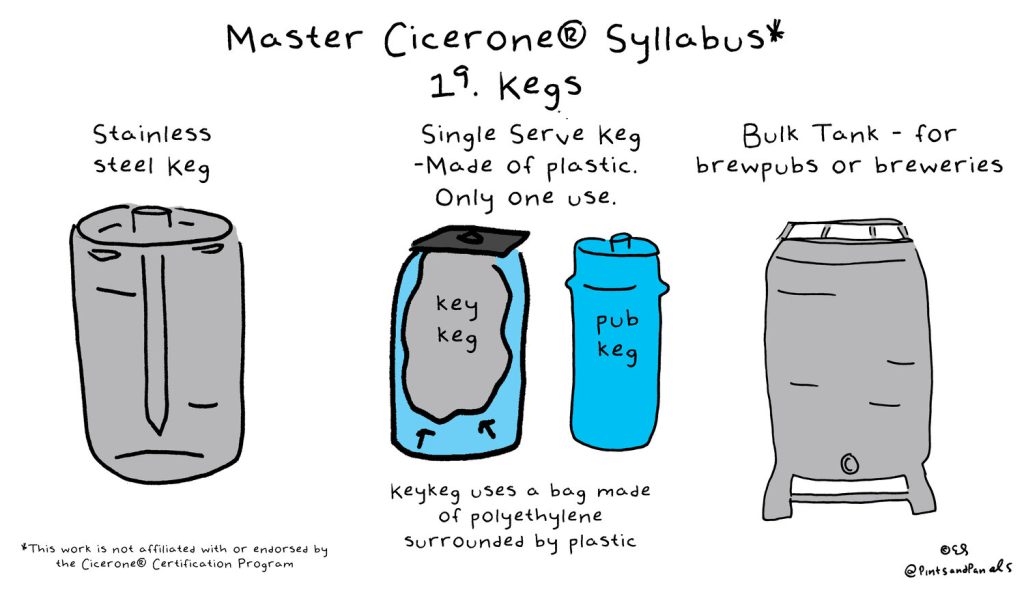

Keg. A cylindrical container, usually constructed of steel or sometimes aluminum, commonly used to store, transport and serve beer under pressure. In the U.S., kegs are referred to by the portion of a barrel they represent, for example, a ½ barrel keg = 15.5 gal, a ¼ barrel keg = 7.75 gal, a 1/6 barrel keg = 5.23 gal. Other standard keg sizes will be found in other countries.

Kilning. The process of heat-drying malted barley in a kiln to stop germination and to produce a dry, easily milled malt from which the brittle rootlets are easily removed. Kilning also removes the raw flavor (or green-malt flavor) associated with germinating barley, and new aromas, flavors, and colors develop according to the intensity and duration of the kilning process.

Kraeusen n – The rocky head of foam which appears on the surface of the wort during fermentation. v – A method of conditioning in which a small quantity of unfermented wort is added to a fully fermented beer to create a secondary fermentation and natural carbonation.

L

Lace. The lacelike pattern of foam sticking to the sides of a glass of beer once it has been partly or totally emptied. Synonym: Belgian lace

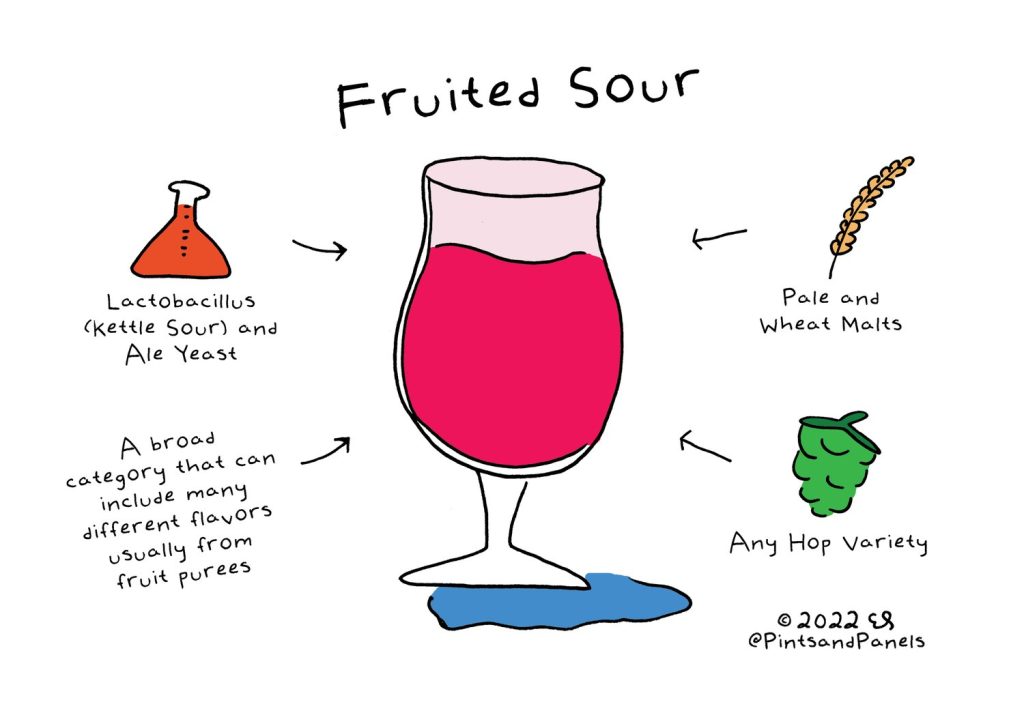

Lactobacillus. A microorganism/bacteria. Lactobacillus is most often considered to be a beer spoiler, in that it can convert unfermented sugars found in beer into lactic acid. Some brewers introduce Lactobacillusintentionally into finished beer in order to add desirable acidic sourness to the flavor profile of certain brands.

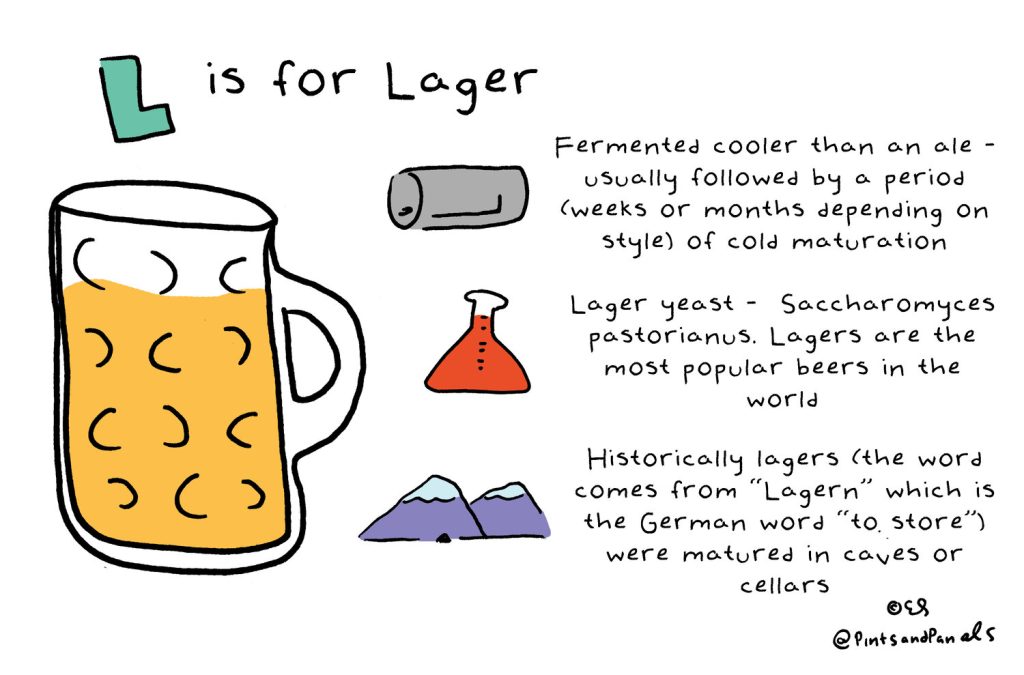

Lager. Lagers are any beer that is fermented with bottom-fermenting yeast at colder temperatures. Lagers are most often associated with crisp, clean flavors and are traditionally fermented and served at colder temperatures than ales.

Lager Yeast. Saccharomyces pastorianus is a bottom fermenting yeast that ferments in cooler temperatures (45-55 F) and often lends sulfuric compounds.

Lagering. Storing bottom-fermented beer in cold cellars at near-freezing temperatures for periods of time ranging from a few weeks to years, during which time the yeast cells and proteins settle out and the beer improves in taste.

Large Brewery. As defined by the Brewers Association: A brewery with an annual beer production of over 6,000,000 barrels.

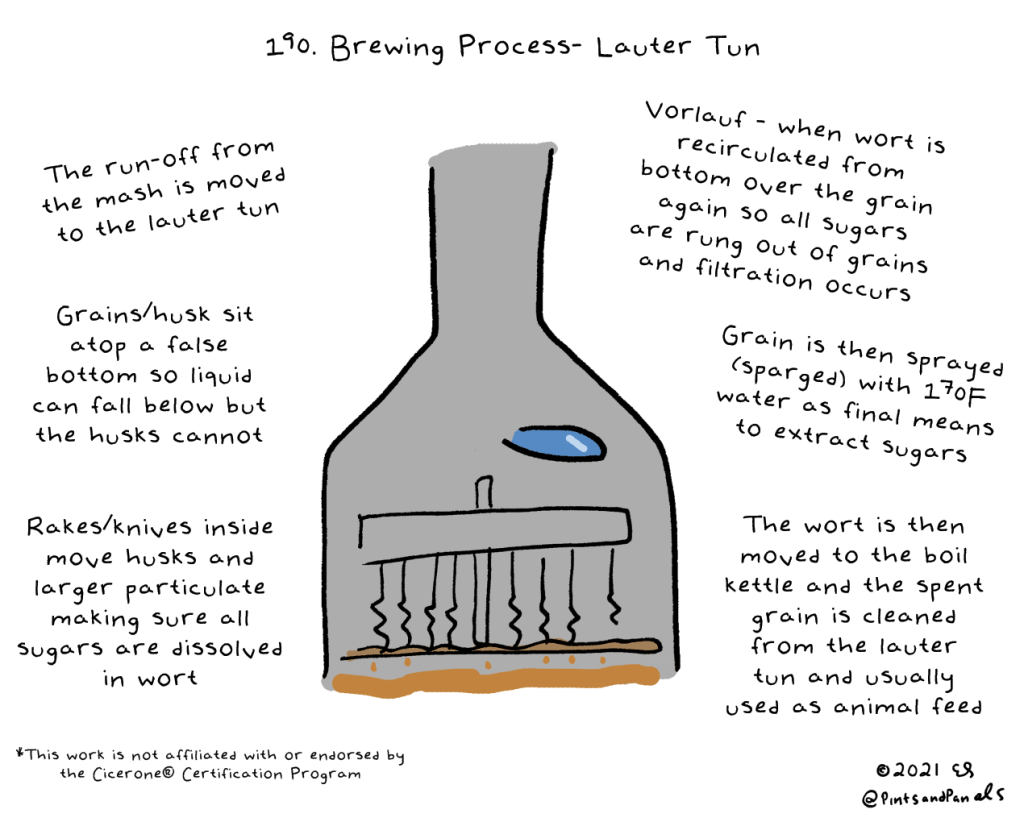

Lauter Tun. A large vessel fitted with a false slotted bottom (like a colander) and a drain spigot in which the mash is allowed to settle and sweet wort is removed from the grains through a straining process. In some smaller breweries, the mash tun can be used for both mashing and lautering.

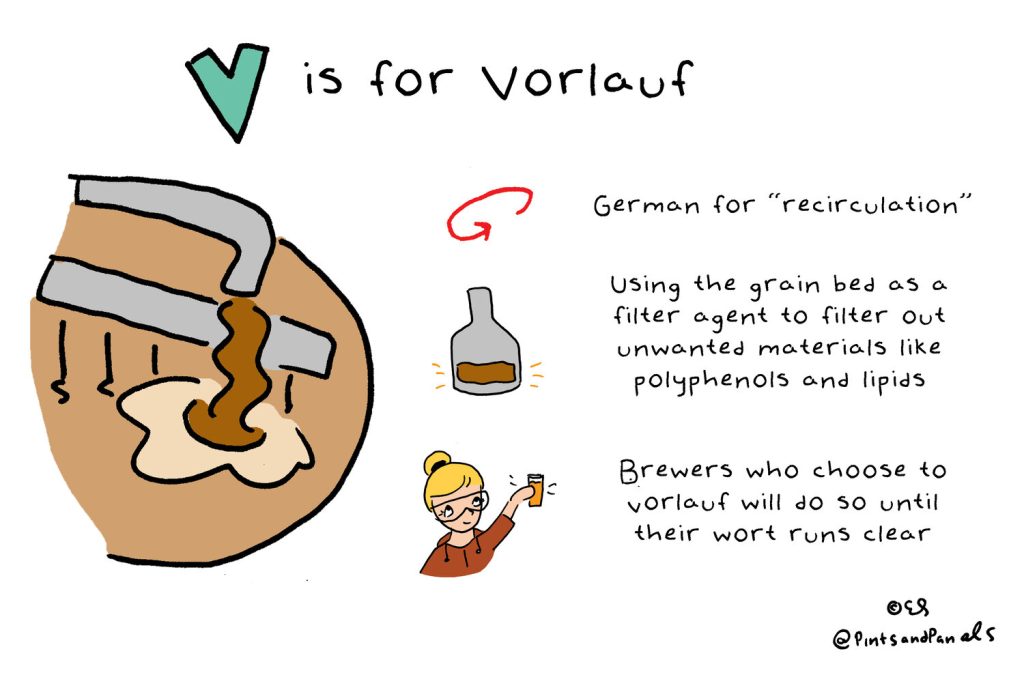

Lautering. The process of separating the sweet wort (pre-boil) from the spent grains in a lauter tun or with other straining apparatus.

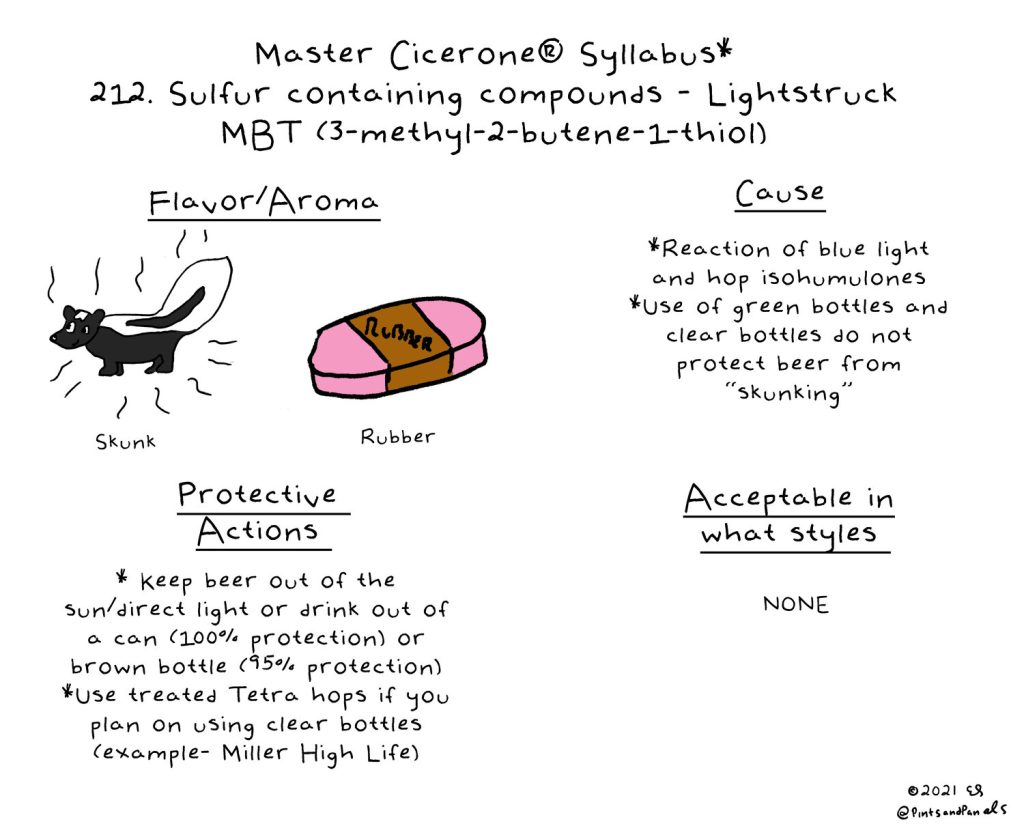

Lightstruck (Skunked). Appears in both the aroma and flavor in beer and is caused by exposure of beer in light colored bottles or beer in a glass to ultra-violet or fluorescent light.

Liquor. The name given, in the brewing industry, to water used for mashing and brewing, especially natural or treated water containing high amounts of calcium and magnesium salts.

Lovibond. A scale used to measure color in grains and sometimes in beer. See also Standard Reference Method.

M

Magnum Bottle. A 1.5L bottle

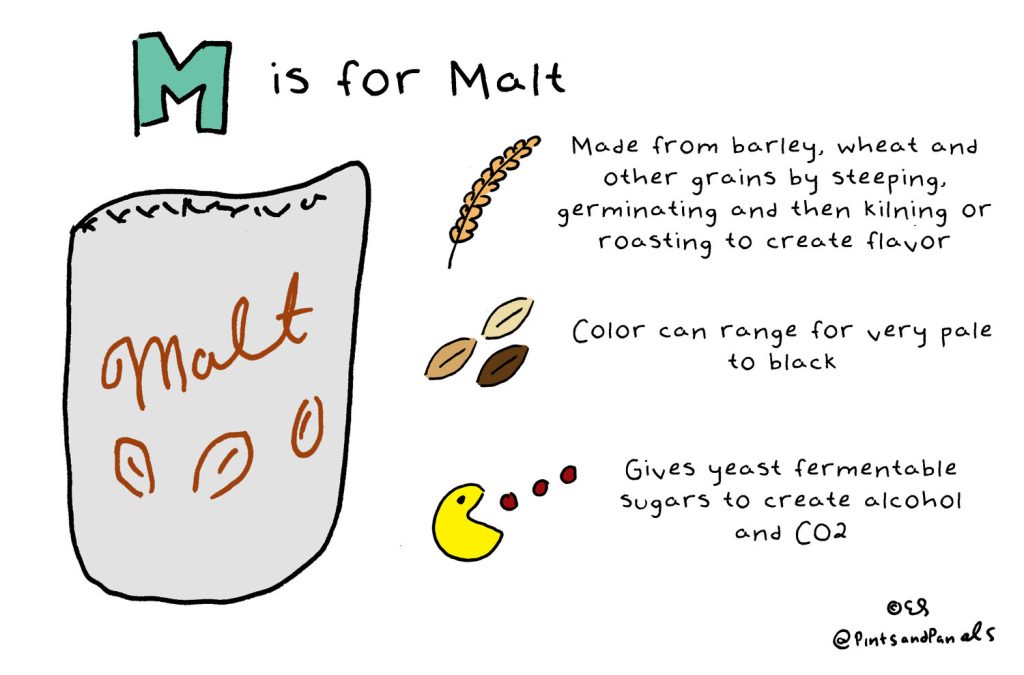

Malt. Processed barley that has been steeped in water, germinated on malting floors or in germination boxes or drums, and later dried in kilns for the purpose of stopping the germination and converting the insoluble starch in barley to the soluble substances and sugars in malt.

Malt Extract. A thick syrup or dry powder prepared from malt and sometimes used in brewing (often used by new homebrewers).

Maltose. The most abundant fermentable sugar in beer.

Mash. A mixture of ground malt (and possibly other grains or adjuncts) and hot water that forms the sweet wort after straining.

Mash Tun. The vessel in which grist is soaked in water and heated in order to convert the starch to sugar and to extract the sugars, colors, flavors and other solubles from the grist.

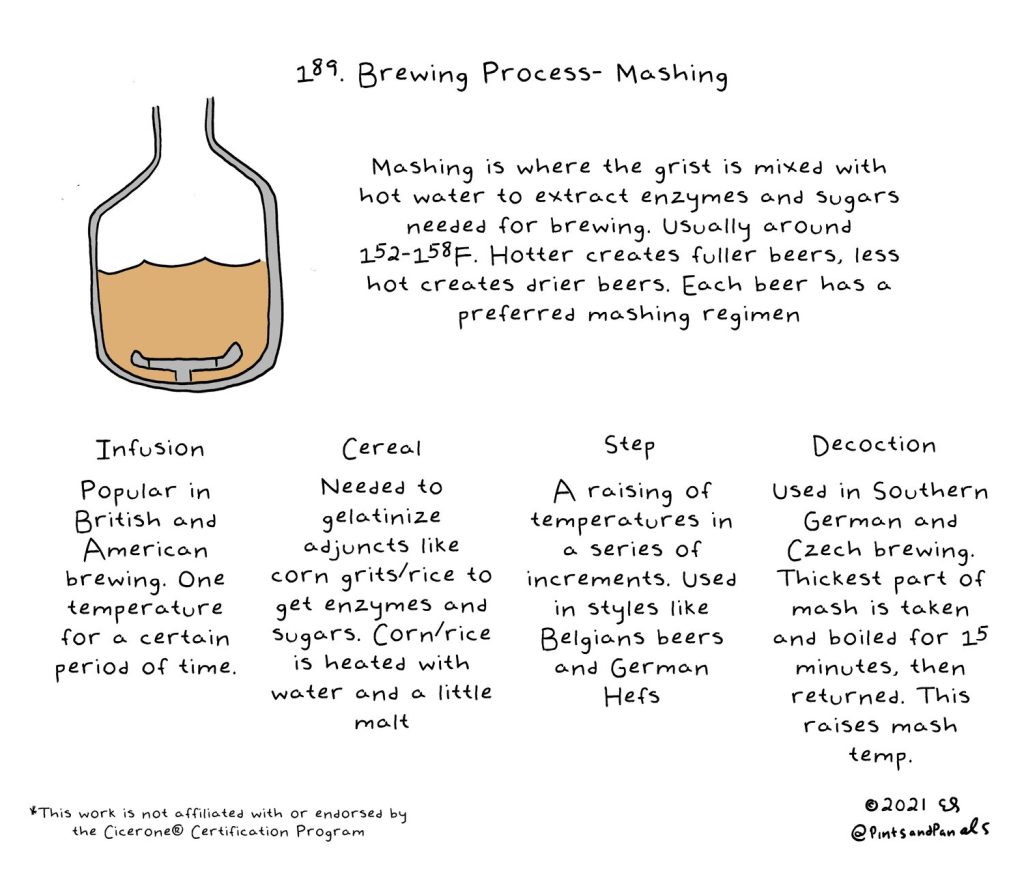

Mashing. The process of mixing crushed malt (and possibly other grains or adjuncts) with hot water to convert grain starches to fermentable sugars and non-fermentable carbohydrates that will add body, head retentionand other characteristics to the beer. Mashing also extracts colors and flavors that will carry through to the finished beer, and also provides for the degradation of haze-forming proteins. Mashing requires several hours and produces a sugar-rich liquid called wort.

Mashing Out. The process of raising the mash temperature to 170F. The goal is to halt any enzymatic activity and prevent further conversion of starches to sugars.

MBAA. Master Brewers Association of the Americas (MBAA) was formed in 1887 with the purpose of promoting, advancing, and improving the professional interest of brew and malt house production and technical personnel.

Microbrewery. As defined by the Brewers Association: A brewery that produces less than 15,000 barrels of beer per year with 75 percent or more of its beer sold off-site.

Milling. The grinding of malt into grist (or meal) to facilitate the extraction of sugars and other soluble substances during the mash process. The endosperm must be crushed to medium-sized grits rather than to flour consistency. It is important that the husks remain intact when the grain is milled or cracked because they will later act as a filter aid during lautering.

Modification.

- The physical and chemical changes in barley that result from malting, especially the development of enzymes that are required to modify the grain’s starches into sugars during mashing, and also the physical changes that render the carbohydrate found in barley kernels more available to the brewing process.

- The degrees to which these changes have occurred, as determined by the growth of the acrospire.

Modified Malts. Modified Malts refers to the length of the germination process and how many of the internal malt structures and compounds have already been broken down.

Mouthfeel. The textures one perceives in a beer. Includes carbonation, fullness and aftertaste.

Musty. Moldy, mildewy character that can be the result of cork or bacterial infection in a beer. It can be perceived in both taste and aroma.

Myrcene. One of the essential oils made in the flowering cone of the hops plant Humulus lupulus.

N

Natural Carbonation Sugar is added to beer in its container and then sealed. Fermentation kicks off again as the yeast eats the new sugar addition. When yeast ferments, it releases CO2 which is then absorbed into the liquid.

Ninkasi. The ancient Sumerian goddess of beer.

Nitrogen. When used for the carbonation of beer, Nitrogen contributes a thick creamy mouthfeel, different from the mouthfeel you get from CO2.

Noble Hops. Traditional European hop varieties prized for their characteristic flavor and aroma. Traditionally these are grown only in four small areas in Europe:

- Hallertau in Bavaria, Germany

- Saaz in Zatec, Czech Republic

- Spalt in Spalter, Germany

- Tettnang in the Lake Constance region, Germany

O

Oasthouse. A farm-based facility where hops are dried and baled after picking.

Original Gravity (OG). The specific gravity of wort before fermentation. A measure of the total amount of solids that are dissolved in the wort as compared to the density of water, which is conventionally given as 1.000 and higher. Synonym: Starting gravity; starting specific gravity; original wort gravity.

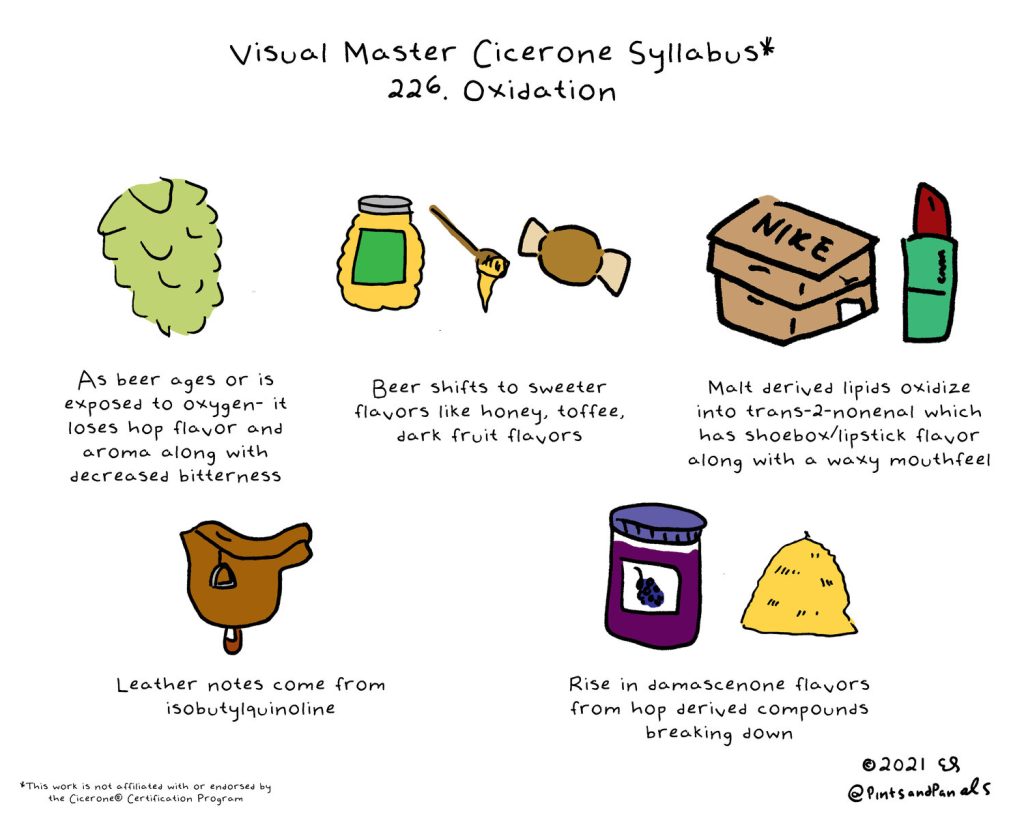

Oxidation. A chemical reaction in which one of the reactants (beer, food) undergoes the addition of or reaction with oxygen or an oxidizing agent.

Oxidized. Stale, winy flavor or aroma of wet cardboard, paper, rotten pineapple sherry and many other variations.

P

Package. A general term for the containers used to market beverages. Packaged beer is generally sold in bottles and cans. Beer sold in kegs is usually called draught beer.

Palate. The top part of the inside of your mouth and is generally associated with how humans taste.

Pediococcus. A microorganism or bacteria usually considered contaminants of beer and wine although their presence is sometimes desired in beer styles such as Lambic. Certain Pediococcus strains can produce diacetyl, which renders a buttery or butterscotch aroma and flavor to beer, sometimes desired in small doses, but usually considered to be a flavor defect.

pH. Abbreviation for potential Hydrogen, used to express the degree of acidity and alkalinity in an aqueous solution, usually on a logarithmic scale ranging from 1-14, with 7 being neutral, 1 being the most acidic, and 14 being the most alkaline.

Phenols. A class of chemical compounds perceptible in both aroma and taste. Some phenolic flavors and aromas are desirable in certain beer styles, for example German-style wheat beers in which the phenolic components derived from the yeast used, or Smoke beers in which the phenolic components derived from smoked malt. Higher concentrations in beer are often due to the brewing water, infection of the wort by bacteria or wild yeasts, cleaning agents, or crown and can linings. Phenolic sensory attributes include clovey, herbal, medicinal or pharmaceutical (band-aid).

Pitching. The addition of yeast to the wort once it has cooled down to desirable temperatures.

Primary Fermentation. The first stage of fermentation carried out in open or closed containers and lasting from two to twenty days during which time the bulk of the fermentable sugars are converted to ethyl alcohol and carbon dioxide gas. Synonym: Principal fermentation; initial fermentation.

Priming. The addition of small amounts of fermentable sugars to fermented beer before racking or bottling to induce a renewed fermentation in the bottle or keg and thus carbonate the beer.

Prohibition. A law instituted by the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (stemming from the Volstead Act) on January 18, 1920, forbidding the sale, production, importation, and transportation of alcoholic beverages in the U.S. It was repealed by the Twenty-first Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on December 5, 1933. The Prohibition Era is sometimes referred to as “The Noble Experiment.”

Punt. The hollow at the bottom of some bottles.

Q

Quaff. To drink deeply.

R

Racking. The process of transferring beer from one vessel to another, especially into the final package or keg.

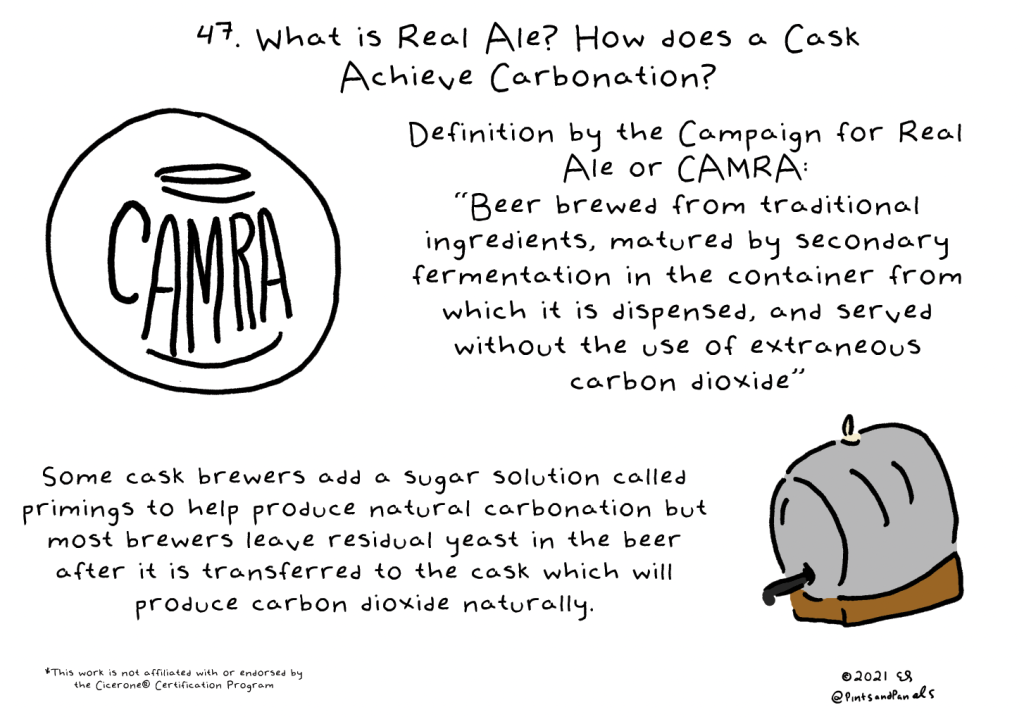

Real Ale. A style of beer found primarily in England, where it has been championed by the consumer rights group called the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA). Generally defined as beers that have undergone a secondary fermentation in the container from which they are served and that are served without the application of carbon dioxide.

Regional Craft Brewery. As defined by the Brewers Association: An independent regional brewery having either an all malt flagship or has at least 50 percent of its volume in either all malt beers or in beers which use adjuncts to enhance rather than lighten flavor.

Reinheitsgebot. The German beer purity law passed in 1516, stating that beer may only contain water, barley and hops. Yeast was later added after its role in fermentation was discovered by Louis Pasteur.

Residual Alkalinity. A measurement of the mash’s ability to buffer, or resist, attempts to lower its pH.

Residual Sugar. Any leftover sugar that the yeast did not consume during fermentation.

Resin. The gummy organic substance produced by certain plants and trees. Humulone and lupulone, for example, are bitter resins that occur naturally in the hop flower.

S

Saccharification. The conversion of malt starch into fermentable sugars, primarily maltose.

Saccharomyces. The genus of single-celled yeasts that ferment sugar and are used in the making of alcoholic beverages and bread. Yeasts of the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces pastorianus are commonly used in brewing.

Secondary Fermentation:

- The second, slower stage of fermentation for top fermenting beers, and lasting from a few weeks to many months, depending on the type of beer.

- A renewed fermentation in bottles or casks and initiated by priming or by adding fresh yeast.

Sediment. The refuse of solid matter that settles and accumulates at the bottom of fermenters, conditioning vessels and bottles of bottle-conditioned beer.

Session Beer. A beer of lighter body and alcohol of which one might expect to drink more than one serving in a sitting.

Solvent-like. Flavor and aromatic character similar to acetone or lacquer thinner, often due to high fermentation temperatures.

Sorghum. A cereal grain from various grasses (Sorghum vulgare). Also a grain sought out by those who are gluten intolerant.

Sour. A taste perceived to be acidic and tart. Sometimes the result of a bacterial influence intended by the brewer, from either wild or inoculated bacteria such as lactobacillus and pediococcus.

Sparging. In lautering, an operation consisting of spraying the spent mash grains with hot water to retrieve the liquid malt sugar and extract remaining in the grain husks.

Specific Gravity. The ratio of the density of a substance to the density of water. This method is used to determine how much dissolved sugars are present in the wort or beer. Specific gravity has no units because it is expressed as a ratio. See also Original Gravity and Final Gravity.

Standard Reference Method (SRM). An analytical method and scale that brewers use to measure and quantify the color of a beer. The higher the SRM is, the darker the beer. In beer, SRM ranges from as low as 2 (light lager) to as high as 45 (stout) and beyond.

Steeping. The soaking in liquid of a solid so as to extract flavors.

Step Infusion. A mashing method wherein the temperature of the mash is raised by adding very hot water, and then stirring and stabilizing the mash at the target step temperature.

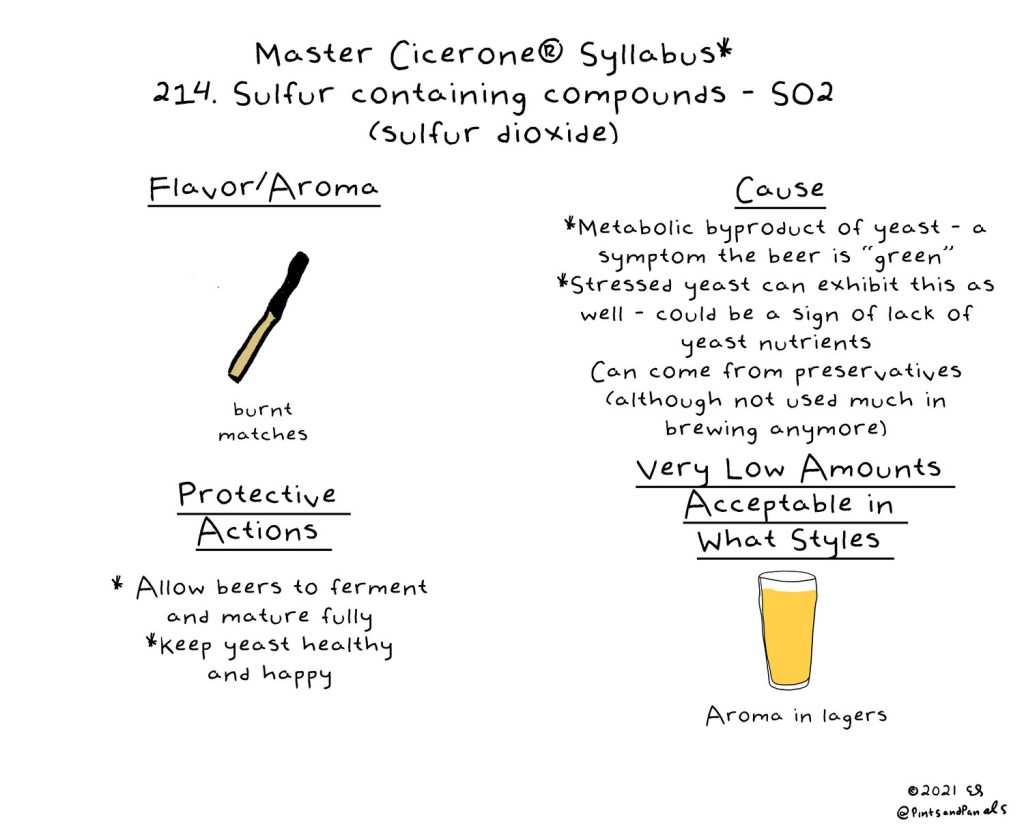

Sulfur. Aroma reminiscent of rotten eggs or burnt matches; a by-product of some yeasts or a beer becoming light struck.

T

Tannins. A group of organic compounds contained in certain cereal grains and other plants. Tannins are present in the hop cone. Also called “hop tannin” to distinguish it from tannins originating from malted barley. The greater part of malt tannin content is derived from malt husks, but malt tannins differ chemically from hop tannins. In extreme examples, tannins from both can be perceived as a taste or sensation similar to sampling black tea that has steeped for a very long time.

Temperature Rests. Temperature Rests during the beer making process allows the brewer to adjust fermentable sugar profiles so as to influence characteristics of the resulting beer.

Top Fermentation. One of the two basic fermentation methods characterized by the tendency of yeast cells to rise to the surface of the fermentation vessel. Ale yeast is top fermenting compared to lager yeast, which is bottom fermenting. Beers brewed in this fashion are commonly called ale or top-fermented beers.

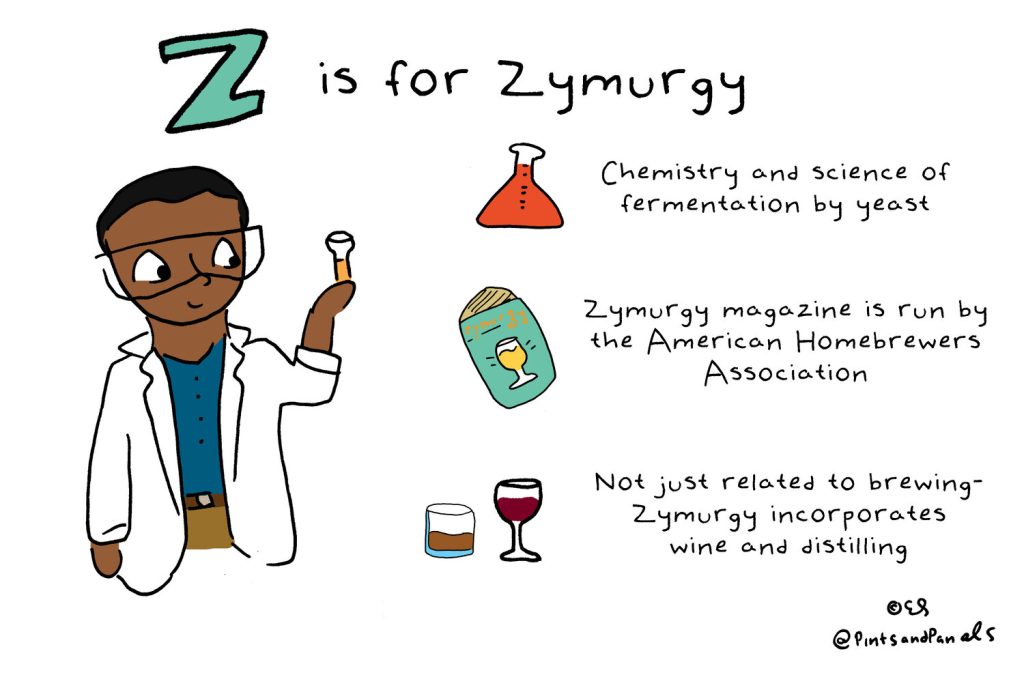

Trigeminal Nerves: